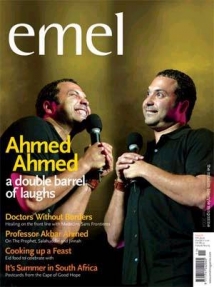

A Double Barrel of Laughs

Issue 8 Nov / Dec 2004

First Published on November/December 2004

To access the issue page, click here

"My friends would come round while my parents were praying and they would be like, 'What are they doing down there? Have they lost something?'"

Ahmed Ahmed strides into the Hampstead Hotel lobby with the air of a man who is used to stepping out into the void. As one of the very few Muslim comedians to have successfully wooed Muslim audiences, Ahmed Ahmed is a rare breed interspersing hilarity with humility, comic sketches with quiet sincerity.

Ahmed Ahmed (yes that really is the name his parents gave him) ha just been at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival and although he’s evidently tired from a relentless tour of the UK, his upbeat demeanour is not in the least tempered by weariness. He launches into an amusing tale of how his family emigrated to the US from Egypt when he was one month old. “I was born just outside Cairo but then we moved to Riverside in California and I never understood why my father moved us from one desert to another desert.” Describing his upbringing as strict and his parents as being extremely devout, the young American- Egyptian Muslim found it difficult to reconcile his hybrid identity. “I definitely had insecurities about being Egyptian and Muslim. Like any kid I just wanted to be normal tian and Muslim. Like any kid I just wanted to be normal and when my friends would come round while my parents happened to be praying they would be like, ‘What are they doing down there? Have they lost something?’ and I would just feel so awkward.” At the age of 19, Ahmed moved to Hollywood to pursue a career in acting, much to his parents’ mortification. “Like all Arab parents they wanted me to be a doctor or an engineer. They weren’t impressed that I wanted to be an actor.” Ahmed persevered with his dream and was eventually eking out a decent living in films and TV. However he soon became disillusioned at the type of work he was getting, “I found that the only roles being offered to me perpetuated the negative stereotype of the Arab terrorist. I was typecast and couldn’t break out of it. There is so much more to Arab and Muslim culture than being a terrorist, but Hollywood isn’t interested in anything else. I found it frustrating having to constantly portray two-dimensional characters that misrepresented my culture.”

Unable to flex his creative muscles, Ahmed felt stifled, unfulfilled and isolated, “living in LA and trying to make it as an actor is a harsh deal when you’re living with the reality of constant disappointment. I began to feel misplaced. It seemed that everybody else had a community that they were part of except me and I felt very alone.” He surfed the shores of an emotional malaise which manifested itself in a re-definition of his spirituality. “I had a kind of vision, which I thought was a bad dream. I told my mother about it and she suggested I go to Hajj which I did and when I was at Mecca I saw a slice of Islam in a new light.” Ahmed is endearingly humble about his personal faith, “I’m not perfect. I try to pray five times a day, keep my intention clear and embrace my belief. Before a gig I always pray and ask Allah for guidance, acknowledging Allah and asking for his help.” Ahmed quit acting and spent the next year waiting tables. “One day an elderly lady came into the restaurant and began telling me I should be a comedian. Something about what she had said really stuck in my mind and a month later I went on stage at the local comedy club for six minutes, just talking about my family. It went down really well and my life as a comedian began there.” Ahmed’s parents were supportive, “having got over the fact that I was an actor I guess when I said I was going to be a comedian it was a case of, ‘there he goes again.’” Ahmed’s typical day is not your usual 9-5, “I get up at noon, start my day by 2pm and then at 10pm I’m off to the Comedy Club to do my gig. It’s an unconventional way of living.”

With the unsocial hours and irregular work, a comedian needs to be passionate about his comedy in order to survive. “No matter how bad life is going – whether you’re running out of money or having problems with people; the block of time on stage and hearing that wave of laughter when you hit the punch-line is pure validation.

That’s what keeps me going.” He reveals a vulnerability that resonates among many comedians, “I am a very insecure person. Most comedians are, although for me it stems from my insecurities about being Egyptian and Muslim when I was younger. The people who prevail in this industry are those who can keep their ego in check. Those who get caught up in the smoke and mirrors and buy into their celebrity are the ones who will have problems.”

His identity is inescapably a defining factor in his work, “I understand the responsibility you have to the culture and faith you come from but I also don’t want to be pigeon-holed.” Ahmed is sensitive to his audience, for example when undertaking the Islamic Relief tour of the UK which included a performance in front of 3200 people at the Royal Albert Hall, Ahmed and his associate at Islamic Relief, “went through my act and made sure that my material was appropriate for a family audience. What may be fine to perform in front of an American non-Muslim audience may not be appropriate for an audience made up of everyone from five year olds to Hajjis.” Ahmed doesn’t see this as censorship, “This is not a reduction of my material but a reflection. People do argue that you’re not supposed to laugh at religion but my humour is self-deprecating, not ridiculing, and one of the best ways to educate people about Islam is through the medium of comedy. If anyone says I’m perpetuating stereotypes I take a step back and though I don’t feel I must explain myself I let them know that what I’m trying to do is make light of the stereotype.” Ahmed admits that almost all of his work is inspired by his own experiences, whether good or bad. “One way of looking at it is that there is actually nothing funny about comedy. It’s a method of healing to take away the pain of past events. You find that when you have a combination of tragedy and time, the result is comedy.”

The events of September 11 instigated an introspective period for Ahmed as he assessed his calling as a comedian in this new climate, “After that happened I took time out. I stayed at home and tried to figure out the consequences. How could I stand up and make jokes about being an Arab Muslim now? It was a confusing time.” It was under the aegis of Comedy Store owner Mitzi Shore, who had discovered David Letterman, Richard Pryor, Jim Carey and Whoopi Goldberg among others, that Ahmed cultivated his role in an atmosphere so altered by the atrocities. “Eleven months before September 11 Mitzi, who is Jewish, contacted myself and two other Arab comedians and asked us to perform at the Comedy Store. She told me she had experienced an epiphany that war was imminent and Arabs would be more misrepresented than ever. Two days before the planes hit the towers she was talking about this war that she felt was coming any day now. The Friday after the attacks she opened the Comedy Store and told me I was the first act. She said people will ask questions so go out there and shed light on your people. She then told me to stay at home for a month and re-write my act. I felt the need grow within me to talk about what I know.”Ahmed was catapulted into the limelight when he appeared on the front cover of the Wall Street Journal, a rare honour to be bestowed on an Arab Muslim, “Somebody had to crack the egg. For years we had just been brushed under the rug, although having said that I was quite shocked to see myself on the front page.”

Carving a career as a comedian over the past ten years has undoubtedly been a struggle, but Ahmed is not ready to rest on his laurels and get comfortable now, “I would like to practice spiritual philanthropy and also raise the funds to pursue my own projects.” His ambition is to translate comedy into film and TV. “I’m working on a half hour comedy show that is loosely based on my life. The subliminal message this show is going to send out is that this guy is a Muslim and his life is as ordinary or extraordinary as anyone else’s.”

His biggest dream however is to write, direct, and open a restaurant! “My parents owned a restaurant while I was growing up and those experiences feature heavily in my comedy. I guess it’s like that whole thing about not being able to hate something when you’re laughing about it. That’s my own form of redemption.”

Bookmark this |

|

Add to DIGG |

|

Add to del.icio.us |

|

Stumble this |

|

Share on Facebook |

|

Share this |

|

Send to a Friend |

|

Link to this |

|

Printer Friendly |

|

Print in plain text |

|

Comments

0 Comments