The People's Scholar

Issue 8 Nov / Dec 2004

First Published on November/December 2004

To access the issue page, click here

“God did not send Muhammad as ‘the great warrior’ to kill all his enemies; nor did he send him as ‘the great terror’ to terrify his opponents.”

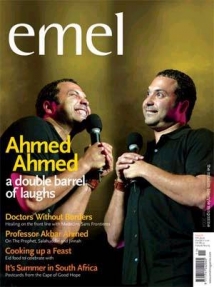

Akbar Salahuddin Ahmed is a man of many talents: scholar, broadcaster, diplomat. An anthropologist by training he is now the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies and Professor of International Relations at the American University in Washington. He is a consummate communicator; his greatest skill being able to simplify, clarify and above all explain to ordinary people the complex ideas and thoughts that dominate our world. On a visit to the UK earlier this year he spoke to Mahmud Al-Rashid about the crisis in the Muslim world and suggests a way out for today’s under siege Muslims.

Akbar Ahmed is walking a tightrope; but for someone who has previously pacifi ed the tribes of Waziristan in Pakistan, he is well suited to his present endeavour. In July this year he toured the UK with Professor Judea Pearl, father of Daniel Pearl, the US journalist killed by religious extremists in Pakistan. Akbar has chosen this tragic incident to accelerate the much needed dialogue and interaction between the Jewish and Muslim communities. “It wasn’t always like this,” he reminds me. “In the past relations between these two Abrahamic faiths was good, even friendly. There was genuine cooperation between Muslims and Jews. You only have to study the era in Spain until 500 years ago to see that. I have been re-reading the life of Sultan Salahuddin (Saladin) and the first major act he did after freeing Jerusalem from the Crusaders was to invite the Jews back in. The great Jewish rabbi and philosopher Maimonides went on to become an adviser to the court of Salahuddin. This is in stark contrast to how the Christians of Europe treated the Jews: the holocaust was the culmination of years of persecution.”

So what went wrong? I ask, expecting perhaps an indecisive answer. “Israel,” he states categorically. “The creation of the state of Israel has soured relations between Muslims and Jews. It has created an intellectual, social and political crisis from which the Muslims of the Middle East especially have not yet extricated themselves. Ever since then there has been deep hostility between Jews and Muslims the world over.”

In Akbar’s view no fair solution will result until both parties are willing to recognise and respect the rights of the other. “In my opinion we need to develop compassion and understanding with Israel so they can understand our position. When I look at what is happening to the Palestinians and their reaction, I get very upset and confused. When I see a mother crying for her son I don’t ask whether she’s Jewish or Muslim. I feel very sad that another innocent human has been killed. That in turn is going to generate more anger, more hatred of Islam - of my civilisation. We need to try and dampen the violence, the hatred, the sense of anger against Muslims, and we can only do this if we become more self conscious of our actions and the effect it has on the non-Muslims”

Akbar is heavily engaged in interfaith dialogue. “The Qur’an is clear that the same level of reverence is due to all the prophets,” he states. “The prophet Muhammad had the highest respect for Jews and Christians – they were representatives of Islam, after all. Islam is the culmination of the Abrahamic tradition – we Muslims share the legacy and traditions of the Jews and Christians. I feel comfortable with them because I understand where they are coming from. But they have problems because for Jews it comes to an end with Moses and they have had serious problems in the past with Christians. Likewise with the Christians – they believe they have an exclusive message and so have had problems with Islam for the last thousand years. Only in 1960 did the Pope recognise Islam as a religion. Christianity and Judaism have both had difficulties adjusting to Islam.”

Akbar mentions his exhilarating interactions with the Chief Rabbi who recently sent him his book The Dignity of Difference with the inscription ‘In great admiration and cherished friendship’. “I felt deeply honoured,” Akbar confides. “We had never met, yet he was reaching out to talk, to discuss, to understand. We went to the Islamia School in London and then the Jewish Free School. We spoke to the children about the common features of our two religions. It is vital that young people see positive interaction and not just the hatred and mutual suspicion that exist.” Akbar acknowledges that some people within the Muslim community are suspicious of his actions, “but the Chief Rabbi has the same problems,” he declares. “There are Jewish people who do not want any interaction with Muslims. But we need to redouble our efforts to engage in genuine debate and dialogue. That is the true Islamic tradition: to engage the hearts and minds, not to create fear and turmoil.”

But what about the oppression of the Palestinians and Muslim peoples around the world? One can dialogue all day and night from the comfort of armchairs, but that is not going to stop the killings and destruction. “I understand the anxiety and the anger of the Muslims, especially the youth. I spend time talking and listening to them; I visit the campuses; I am aware of their feelings. I try to imagine how I would react if my wife or daughter was systematically assaulted and ill-treated. But I must maintain there is only one way forward for Muslims – and that is the example of the insan-e-kamil (the ideal human), which the prophet Muhammad was. Justice and compassion guided all his actions, and so they must ours.”

Muhammad is Akbar’s greatest hero. There is a lesson in his life for every situation. He was motivated by the desire to improve the human condition. That is why he was labelled by God as ‘mercy unto mankind’, and Akbar makes a point here. “Those Muslims who want to fight the west with violence should recall that God did not send Muhammad as ‘the great warrior’ to kill all his enemies; nor did he send him as ‘the great terror’ to terrify his opponents. The choice of words describing Muhammad’s purpose and mission is crucial – he was the ‘mercy unto mankind.’ We need to remember this constantly.”

Salahuddin is Akbar’s second hero. He exemplified all that is best in a Muslim ruler: strength, compassion and the pursuit of justice. “Justice is of paramount interest for the Muslim ruler. The Mughal emperors were an imperial power, unelected by the people. Nevertheless they were mindful of their primary duty: to ensure justice. The emblem on their thrones was not of lions (like the Pahlavis or the British), nor the sword (like the Saudis), but of the scales of justice. A thousand years before Palmerston, Disraeli and Gladstone, the Mughal emperors were sitting there with the scales of justice as their guiding motto. They were reminding themselves that their duty was to ensure justice for the people, otherwise they were not fulfilling God’s commands.”

“Salahuddin embodies that spirit. Even in western scholarship he is above reproach: in Dante’s Inferno he is the only Muslim not in Hellfi re. After the victory over Jerusalem, there were hundreds and thousands of captive crusaders. Salahuddin was under pressure to execute those that could not buy their freedom (as was the rule of war at the time). Instead, the great sultan paid for their freedom from his own money. He had every reason and all the support to execute those pillaging crusaders, but his compassion won through. Can the Muslims of today display such compassion?”

The story is told of how during one of the battles with Richard I, the king had been dismounted and stood staring at defeat. Salahuddin saw this and ordered one of his lieutenants to take two of the fi nest steeds to Richard, declaring that ‘even in defeat, honour dictates that a king should not have to walk’. Despite all the opportunity to be wealthy, Salahuddin died possessing a sword, a saddle, a Qur’an and 70 dirhams. He had a great love for knowledge and would spend his evenings with the scholars in the madrassas.

The recurrent theme in Akbar’s speeches and writings is Islam’s unique emphasis on ilm (knowledge), adl (justice) and ihsan

(compassion) as the foundation of a religious life. “There’s a massive failure of Muslim scholarship and leadership,” he

laments. “In bygone eras Muslim scholars would set their leaders straight or die in the process. They never compromised on the fundamentals of ilm, adl and ihsan. Four of the greatest scholars – Abu Hanifa, Shafi, Malik and Hanbal (after whom four leading schools of thought are named) all faced agonising problems with the rulers of their day. They were threatened and punished, but they remained constant in reminding the rulers of the need for ilm, adl and ihsan,” Akbar recounts. “Contrast that with many of today’s scholars who are either in exile from Muslim countries or are sycophantic to the rulers. The pursuit of ilm is not encouraged.

Once, there were 40 thousand scholars based in Bukhara. Once, there were more books in a single Muslim library in Cordoba than in the rest of Europe; now my university in America has more books than the whole of Pakistan. This is the dire position of ilm in the Muslim world today.”

There are courageous scholars, but they talk in the language of the 11th and 12th centuries. I meet so many young people who are facing intense problems of discrimination and insecurity and are thirsting for modern explanations. Answers from 10th century Arabia has no relation to 21st century USA.”

Akbar is equally excoriating of Muslim rulers. “Most of them enjoy no legitimacy with their own people; they are either military dictators or hereditary monarchs. They exercise no justice and show no compassion. There is maladministration and an entrenched disrespect for the concepts of ilm, adl and ihsan. So many Muslim rulers have mansions and villas in western countries yet they have done nothing to advance the understanding of Islam in those countries. Take, for example, the USA. In a post 9/11 survey it was revealed that 80% of Americans knew nothing about Islam! Whose fault is that? What have the Muslim rulers with all their wealth done to educate the people about Islam?”

In this respect Akbar is doing his fair share. He has addressed members of Congress at the bipartisan Congressional retreat in Greenbrier. He has lectured at the National Defense University, Foreign Service Training Institute, and the State Department. He has conducted courses on Islam for the Society of Fellows Seminar and the Socrates Society at the Aspen Institute, the Young President’s Organization, and the World Bank.

It all started in 1980. “What changed my life was my father – he was a fi ne example of a Muslim and he inspired me. A successful senior official, he was in the imperial railway service, and then director of the UN in Bangkok. He was humble, simple, and tolerant and spoke to people from all backgrounds. I witnessed all this. He never drank and so I grew up teetotal. He’d always say his prayers without making a fuss. He was keen for me to write on Islam, but I was reluctant. Tension mounted because we were very close and I always listened to him. At the height of my Civil Service of Pakistan (CSP) career I was about to be posted to Khyber, my father told me to do my PhD otherwise I would remain intellectually unfulfilled. I said no, making weak excuses. However, I relented and came to SOAS, London. He kept persisting about writing a book on Islam. I was resisting because I was an anthropologist, I wrote about tribes and ethnicities, social organisations, etc. not on Islam.”

“I then went to Princeton Institute of Advanced Studies in the USA (only the second Pakistani to be invited there) where I wrote on the tribes of Waziristan. In 1980 I received news that my father was unwell in Karachi. I informed my family that I was coming, but then my brother rang to say my father had died. This shocked me, and I still haven’t fully got over it. His passing away has left a tremendous vacuum in my life. I remember my reaction; the phone dropped from my hand. I am normally good at crises, but on this occasion I was in a trance. I walked absent-mindedly to my offi ce and started to scribble on some paper. A friend walked into my office, asked what I was doing. I replied that I was writing a book on Islam. ‘But you’ve always said you’re not a scholar of Islam,’ she responded. ‘I know, but now I am going to start teaching myself Islam, read its history, travel the Muslim world and write a book.’ She smiled because she knew of the tension with my father. It then took me eight years to write Discovering Islam: Making sense of Islam and Muslim History, published in 1988.” The book has not been out of print since, and the six-part BBC TV series Living Islam was based on this book.

Before 1980 Akbar was writing straight forward anthropology; he became one of world’s most famous anthropologists, being invited to join the legendary figures in Anthropology’s Hall of Fame as part of the ‘Anthropological Ancestors’ interview series at Cambridge University in July 2004, where he had previously been the Iqbal Fellow. Akbar is the recipient of the Star of Excellence in Pakistan and the Sir Percy Sykes Memorial Medal given by the Royal Society of Asian Affairs in London. He is also the recipient of the 2002 Free Speech Award given by the Muslim Public Affairs Council, the 2004 Gandhi Center Fellowship of Peace Award. He was given the 2004 Scholar of the Year Award by the Pakistani-American Congress.

Akbar’s third hero is Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan. “Jinnah was an enigma, a mystery, a paradox. He started life in one position and ended up somewhere else. He was a westernised lawyer, part of the elite jet-setting society of Bombay and married to a non-Muslim. In the 1920s the poet-philosopher Iqbal rebuked him for not representing the community. Jinnah left India in disgust and spent the early 30s sitting in England. Then an Islamic ember began to burn inside him, and by time he returned to India and reorganised the Muslim League in 1937 he had discovered his Islamic identity. In my book Jinnah, Pakistan and an Islamic Identity, I point out that there is a very strong correlation between his discovery of Islam in the twilight of his life and his connection to the community. He began to dress and speak in a way the people understood. By early 1940s this Anglicised, remote leader who couldn’t even speak the language of his people had totally transformed himself. His famous address in Lahore in 1940 was in English, yet the people were mesmerised. For my documentary on Jinnah I interviewed people who were there at that speech. His integrity made an impact on the Muslims. They felt he was someone who could balance the force of Gandhi.”

“For me,” Akbar continues, “Jinnah presents a model for today’s Muslims in his principled stand and the use of constitutional means to bring about change. He could have resorted to violence – some of his followers were the Baluchi, a warrior race with a tradition of fighting; he simply had to give them the nod, but instead he chose the legitimate way – the way of the insan-e-kamil.”

Akbar is an admirer of Gandhi too. “He was a man we Muslims must appreciate more. We have made a caricature out of him like many Hindus have done of Jinnah. The relation between Gandhi and Jinnah wasn’t a simple black and white one. They were not two foes, rather two worthy opponents – with two distinct ways of looking at politics. There was a very famous incident when they met in the presence of all the media. 'You have mesmerised the Muslims,' Gandhi teased Jinnah, who retorted quick as a flash 'And you, Gandhi, have hypnotised the Hindus.'

When Gandhi died Jinnah declared the Muslims had lost their greatest friend. I believe it is time for Hindus to appreciate Jinnah more and the Muslims to give Gandhi his due recognition.”

We return to the theme of the current Muslim disarray. Akbar has a thesis; he says it’s controversial and he expounds it in his recent book Islam Under Siege: Living Dangerously in a Post-Honor World. “God has different sets of commands for us on earth. The first set establishes the vertical relationship between the individual and the Creator – they form what is popularly known as the five pillars; they can be done individually and they increases one’s personal piety. Then there is the horizontal relationship, a set of commands which involves relationships with people in society – they are adl, ihsan and ilm. You cannot do adl (justice) on your own, it requires you to act with your neighbour, your society, or as a ruler, a professional, a father, as a friend. You cannot exercise ihsan (compassion) without engaging with people, and you cannot acquire or impart ilm (knowledge) without your fellow humans. Adl, ihsan, and ilm must form the social fabric.”

“My thesis is that Muslims are succeeding in some parts of the world in respect of developing the vertical relationship; they are great believers, but they are not succeeding in the horizontal relationship. That is where the imbalance exists. In my opinion this asymmetry is causing problems in Muslim society. For example, you could not fault the Taleban in respect of their obedience to the first set of commands, but they were a miserable failure in respect of the second set: they were oppressive towards the Tajiks; their treatment of women was appalling; their cruelty towards people who they deemed not to be practicing their version of Islam was shocking. The balance is not there in the Muslim world and the scholars must help the rulers not only to prop up the five pillars but to rebuild the entire building of Islam based on adl, ilm and ihsan. These are the central features of Islam and we don’t see much of them in the Muslim world. All our time is spent on highly charged political discussions which are very sterile and not leading anywhere; we have to pull back from the brink and rediscover our own roots.”

Akbar explains the title of his book, Islam Under Siege. “The ordinary Muslim is between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand his own ruler enjoys no legitimacy, has no compassion and is often tyrannical and brutal. On the other hand he sees the western powers attacking, bombing and killing friends and relatives, taking his country’s resources, keeping his people under economic subjugation. His ruler does not want to listen to him and the world does not understand him. His sense of dignity has been ripped away. His honour has been defiled. No one represents him; no one speaks for him.”

Akbar explains the title of his book, Islam Under Siege. “The ordinary Muslim is between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand his own ruler enjoys no legitimacy, has no compassion and is often tyrannical and brutal. On the other hand he sees the western powers attacking, bombing and killing friends and relatives, taking his country’s resources, keeping his people

under economic subjugation. His ruler does not want to listen to him and the world does not understand him. His sense of dignity has been ripped away. His honour has been defiled. No one represents him; no one speaks for him.”

“Such is the plight of the Muslims,” Akbar expresses forcefully. “We need to understand that. There are forces who want to wipe out Islam, who believe it is the anti-Christ. I debate with them. Islam has to be finished, they say. How are Muslims going to withstand these people, I ask you? We have to dig deep into our rich Islamic heritage and come up with practical answers.”

Akbar is at pains to point out the serious position of the ummah. “Muslims are engaged in conflict with world civilisations: confronting Hindus in South Asia, Jews in the Middle East, Christians in the Balkans, Chechnya, Sudan, Nigeria, evangelists in the USA; there’s conflict in China, rising violence in Europe. In all cases Muslims perceive themselves to be unjustified victims. But the point is we are in a global confrontation with all world civilisations. So either we succeed in conveying to them what Islam is or we stand to be condemned and cut off. We are in the middle of a very critical and dangerous time of world history.”

That is why, in Akbar’s view, so many Muslims admire bin Laden. He challenges the oppressive Muslim rulers and hits back at the west. He gives the people a sense of empowerment, but this is delusional. “Bin Laden is not the answer for Muslims,” Akbar insists. “You cannot change people through hatred, they will only hate you back. And the west can not only hate back, it has the means to inflict a dreadful destruction.” This leads us to talk about the USA. “Americans are generally very open people. Give them a good argument and they will respond. In the US religion plays an important part in political life. Many candidates freely quote the bible and are happy to announce Jesus as their role model. There is the emergence of Christian evangelists – a powerful, organised and established mass of people with a great deal of political clout that is changing the landscape. They can make or break a presidency and Bush reflects their thinking, which is primarily a fundamentalist view of the world that Armageddon is round the corner. When it happens, there will be the second coming of Jesus and there will be peace and prosperity – but only for the Christians, and only their type of Christians, not the Catholics, not Jews and certainly not the Muslims.”

“This is very critical,” Akbar warns, “because this movement of 70-80 million voters has a huge influence on US policy and media. Muslims need to understand this. If they think slitting the throats of Americans is going to work, they are wrong. To these evangelists such actions will only prove that Islam is a barbaric religion that needs to be crushed. Such actions will only feed their hatred, mistrust and fortify their convictions even more. They believe the anti-Christ may well be the Muslims, therefore they must support Israel at all costs, because if there’s no Israel, there can be no reconstruction of the Temple, and if there’s no new Temple then there’s no Jesus. And in order for the Temple to be reconstructed the Mosque must be destroyed, and in order for that to happen the Muslims must be eliminated, and for that to happen, Israel must be supported.”

We move on to pleasanter matters. “One of the happiest moments in my life was when my daughter Amineh got her PhD from Cambridge university in anthropology. She is a Pashtun woman with two children and a loving husband. That day was a moment of immense pride for me.” Akbar has two sons and two daughters. He himself is the eldest of eight children. His wife Zeenat is the grand-daughter of the Wali of Swat. They have been married for 35 years and have shared together the highs and lows of life in the public eye. “Another one of my happiest moments,” Akbar recalls, “was when my university nominated me, out of the hundreds of brilliant professors there, to the 2004 national Professor of the Year Award. Since 9/11 I have been openly speaking about Islam and despite the hostile climate it shows that it is still possible for a Muslim to be nominated for such prestigious awards.”

So how does one sum up such a polymath? The BBC has described him as ‘probably the world’s best-known scholar on contemporary Islam.’ Others call him the new Ibn Khaldun. The political activist George Galloway sent Akbar a copy of his book I’m Not the Only One inscribed with the words “To my brother Professor Akbar. A tower of intellect, strength and integrity. With respect.” In my own view Akbar Ahmed should be credited for bringing the concepts of adl, ihsan and ilm back into mainstream Muslim discourse.

Bookmark this |

|

Add to DIGG |

|

Add to del.icio.us |

|

Stumble this |

|

Share on Facebook |

|

Share this |

|

Send to a Friend |

|

Link to this |

|

Printer Friendly |

|

Print in plain text |

|

Comments

0 Comments