Doctors Without Borders

Issue 8 Nov / Dec 2004

First Published on November/December 2004

To access the issue page, click here

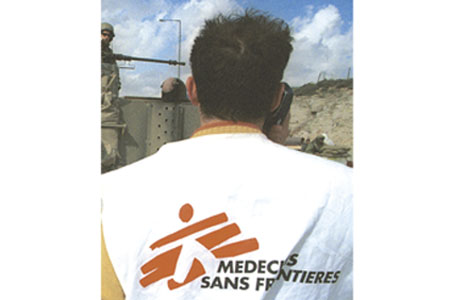

“Neutrality and impartiality is a trade mark of MSF which its volunteers sign up to. Every year about 2,500 trained people leave on worldwide assignments to more than 80 countries.”

Medecins sans Frontieres is an international medical aid agency that has been in existence for more than 30 years. It was founded back in the early 1970s by a group of French doctors who witnessed the tragedy of the war in Biafra and decided that something simply must be done. They decided to create a movement that would deliver urgent aid to wherever it was needed and to speak out against the injustices committed to the victims it helped. Shakina Chowdhury meets people who have risked their lives to save the lives of others.

The term Medecins sans Frontieres simply translates into ‘doctors without borders’, reflecting belief that the right to humanitarian aid transcends barriers of geography, race, class or colour. It is MSF’s stated aim to remain strictly independent of government power and it believes in the right of people to impartial humanitarian assistance. Very often MSF serve the forgotten people, those who don’t make the headlines, so without the help of MSF they would be left to perish. In many situations, the presence of MSF staff and resources means the difference between life and death, a reality which was recognised by the awarding of Nobel Peace Prize in 1999.

After setting up fledgling headquarters in Paris, MSF now has international offices across Europe, Asia, the US and even Australia. These bases are used to recruit volunteers, raise funds and work with the media in spreading their message.

Medecins sans Frontieres has a simple creed: to help those ravaged by war, disease and disasters by bringing aid in the form of emergency medical treatment, food and water. By constantly monitoring events around the world, MSF is often able to respond immediately to a crisis. A rapid needs assessment is carried out by a small team and medical and logistical priorities are immediately set. Once personnel and equipment are mobilised, MSF can be active on the ground within 24 hours.

In conflict zones MSF maintains an absolutely neutral stance: often their intervention means that hospitals remain open to everybody even in the most dangerous circumstances. In fact, MSF hospitals and clinics are neutral areas where armed combatants are banned. Warring parties are called upon to recognise and respect the neutrality of hospitals, patients and staff.

This respect is not always afforded them however. In July 2004 they were forced to pull out of Afghanistan after fi ve of their aid workers were killed. Although they had provided humanitarian relief through terrible war situations for over 24 years they felt it was no longer possible to work safely there. Speaking at the time, Marine Buissonniere, MSF’s international secretary, blamed in part the US-led coalition for their, “attempts to co-opt humanitarian aid; to use humanitarian aid to win hearts and minds.” Giving the example of a coalition leafl et which pictured an Afghan girl carrying a bag of wheat whilst carrying text which said that for assistance to continue, Afghans needed to report information on the Taliban and al Qaeda. Buissonniere said that the provision of humanitarian aid was no longer viewed as a neutral and impartial act in Afghanistan.

That neutrality and impartiality is a trade mark of MSF which its volunteers sign up to. Every year about 2,500 trained people leave on worldwide assignments to more than 80 countries. These people are not only from the medical and nursing profession, but technical staff such as logistics experts, building engineers, and water and sanitation specialists. According to Jean-Michel Piedagnel, Director of MSF UK, “Many people see us as a white, middle class even Christian organisation, as something they cannot aspire to. We need to dispel that image, and show that we recruit people from all different backgrounds and faiths. In order to widen our doors, we are trying to engage dialogue with Muslim organisations.”

An interesting part of MSF’s work involves bearing witness to the terrible tragedies and scenes that they often observe. This process is known by its French name ‘temoignage’ and it involves speaking out on behalf of the people who are suffering, being present during their distress, listening and understanding. In addition to the medical care provided, temoignage offers the chance to raise awareness of the awful plight of the victims that MSF serves.

Dr Sakib Burza

I did my first mission with MSF in September 2003 and it lasted about ten months. I had had previous experience working with a humanitarian organisation because I’d worked with Doctors Worldwide, a Muslim organisation. I’ve been to Afghanistan three times since 2000, working mainly in Kabul and Kandahar. I was in Kandahar during the American bombing. I’ve been asked ‘why MSF?’. Well, the main reason why I chose to work for MSF is their nonpartisan policy towards giving aid. When they go to any country to work in a relief capacity, they don’t ask about your religious or political affiliations. They simply want to help. And sometimes their presence means the difference between life and death.

I worked as a doctor with MSF and I chose to go to southern Sudan, which is largely populated by Christians. You have to go through a pretty rigorous interview beforehand, where they assess your skills, your suitability and your general ability to cope under extreme situations. They then present you with a list of potential destinations and you choose one of them.

Despite the Muslim-Christian conflict in Sudan, I wanted to go there because I had never worked in Africa before. The country was relatively stable at the time I was there – they were waiting to sign a peace deal with the Muslim north. The vast majority of the people around me were mainly Christian, but this was a never a problem for us. There was another Kenyan Muslim nurse there, and we were always treated with respect. There was a small mosque where we were able to pray, in fact, we helped towards its renovation. Our living conditions were quite basic, we lived in a house built of mud and there was no running water. All our water came from a nearby river, which we had to filter before drinking. We bought most of the food that we ate. There were no luxuries, no communication facilities, no email or phone.

The hospital I worked at was the only one in the district, which had a population of about 250,000. The most common ailments were malaria and TB but MSF were well equipped in terms of appropriate medication for these illnesses, which were after all nothing new in this area.

Our team consisted of myself, a Kenyan surgeon, a nurse from England, then another one from France, two logisticians from France and Italy and a field coordinator from Spain called Diego. It was a good team and we all relied on each other, after all, the facilities were quite basic. There were no X-ray machines, no blood testing facilities. A lot depended on our clinical judgement and we treated accordingly. Most, if not all, the equipment and medicines were provided by MSF.

There were many small highlights of my stay in Sudan but the best thing that will always remain in my memory is a little boy whose life I helped to save. He was born three months pre- maturely along with his twin brother who died at birth. His mother walked for 8 hours after giving birth to bring him to our hospital. Despite being only 26 weeks old we managed, by God’s grace, to care for him so that he could survive. Because he had no name, he was given mine, Sakib, as I was the one mainly responsible for him. When I left, he was a thriving three-month old. I still have a picture of him, my miracle namesake, which I will always cherish.

Dr Sally Hamour

I heard about Medecins sans Frontieres a long time ago and ever since I was a teenager I had a vague idea that I might one day work for them. In June 2003 I went to the Nuba mountains region of central Sudan as a MSF doctor and I spent a total of 9 months there. Although you do have some choice about where you end up, the odds of going to Sudan are pretty high considering the internal strife going on for many years. Coincidentally, my family originates from northern Sudan.

I had some initial reservations about going to a country torn by civil war. The people of the Nuba mountains had traditionally sided with the Christian south with their loyalties. However when I got there I found that my reservations were unfounded in the sense that everyone got on well - you were there to do your job regards of the greater political picture.

I worked at a primary health care centre - there was no hospital - which provided a kind of GP service. A lot of the illnesses were seasonal - malaria, pneumonia and meningitis. About 70% of the patients we saw were children. I was the only doctor there, and our team consisted of six nurses, including three local Nuba nurses and a group of community health workers. A typical day would start off with a ward round at 8 am and then we would do a teaching session for the community workers. This was important because we had to leave something positive behind and what better than much needed medical expertise. A couple of mornings a week I would work at the TB centre. In the afternoons we struggled with the busy outpatients department – typically we would see about 150 outpatients a day. Part of working for MSF involves some administration work – data collection, reporting on progress and doing a monthly report. Some evenings were spent doing this; on other evenings, we would take it in turns to cook.

I speak fluent Arabic, which was an enormous help, but we also had interpreters to translate from English to Arabic and vice versa. There’s no Nuba language as such, they speak a number of local dialects.

We lived in a hut called a tukul, usually made of mud or stone with a grass roof. It was quite comfortable! We had our own bed, table, chair and light. We were lucky in that we had electricity that was solar powered. This meant that we were able to have computer facilities including email, satellite radio and the World Service. There was no running water but we had a decent well that provided us with all our water needs.

If anyone asked me ‘would I recommend MSF?’ I would definitely say yes. MSF is a big organisation and has a very high profile compared to many other humanitarian organisations. They are able to do a lot of effective work in many areas around the world and at the same time they can maintain high standards. In 1999 they won the Nobel Peace Prize, which added to their already exceptional profile.

I had an amazing 9 months in Sudan. The Nuba mountains are breathtakingly beautiful and we were able to go for walks and to sightsee. I liked the simplicity of the rural life, the sky at sunset, listening to the crickets. It was very different to practising medicine here, but it was an experience that I will never forget.

Ahmer Ahmed

I had always wanted to be involved in humanitarian work, but I felt that I did not have any suitable qualifications or experience. I used to work in my brother’s shop and I decided that the best thing to do was to get some relevant skills. Some friends of mine were involved in nursing and when I found out more about it, I decided that perhaps this was a good route to follow to facilitate what I wanted to do.

After I qualified as a nurse I approached several organisations including MSF. They said that I needed further skills so I completed a Diploma in Tropical Nursing at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. I found MSF particularly attractive because they were very good at advertising themselves and seemed very politically aware, despite their impartiality regarding giving aid. The interview process was very rigorous, and after that there was a training programme in Holland that I attended.

I went on two missions for MSF, first in Sudan and then in Palestine. In Sudan I was based inthe western upper Nile region, in an area inhabited mostly by the Nuer tribe. The main aim of going was to set up a diagnostic and treatment centre for the disease predominant in that area, which was kala-azar. This disease, transmitted by sand flies in the bush, was endemic in Sudan as a lot of the tribal conflict took place by bush warfare.

Apart from myself there was one other doctor and a team of staff consisting of local people whom we trained as nurses and lab technicians. Despite being a centre for kala azar treatment we inevitably had to deal with all sorts of illnesses including TB, cancer, meningitis and even gunshot wounds. This came from being the only medical centre for literally hundreds of miles. And of course once people heard that medical care was available they would come from long distances. MSF would fl y in all supplies about once a week. Another of my responsibilities was managing the pharmacy section, which meant checking drug supplies.

I think it is extremely important whom you end up working with as these are the people you will be living and working with on a daily basis. I was very lucky in that I had a great team of people to work with. I think the best part of my time in Sudan was the optimism and the generosity of the local people. You have to constantly remember that the whole reason of your being there is to help improve their lives. Because our mission was a success on the whole the gratitude of the people was really touching to witness. It is a wholly different world out there and you have to forget about the rest of the world. You have to be wholly committed.

For my second mission I was based in Hebron, in Palestine and my main role was as primary health care coordinator. Hebron was the complete opposite to Sudan in that it was like working in a developed country, with the exception of some rural communities. The main objective was to set up a mother-child health care programme that included things like post-natal monitoring, immunisations and weight checks.

Working with MSF gave me exposure to people living in extremely difficult situations. It really opens your minds and compels you to connect with different cultures, different values. It widens your sense of humanity.

Vickie Hawkins, Field coordinator

I have worked for MSF as a field coordinator in a number of different countries including Zimbabwe, China, Pakistan and Afghanistan. The field coordinator’s role is quite diverse and each mission usually has one person dedicated to it.

What does this role involve doing? Essentially a field coordinator role can be likened to that of project manager. It involves managing the overall health care project that MSF has implemented, which very often takes place in refugee settings. In my role I was heavily involved in negotiating terms for the medical staff to do their work. There were all sorts of challenges to this, for example you have to negotiate with the authorities, the community leaders, and even rebel factions in trying to gain access to the people you are trying to help. You have to explain what MSF is , what our aims are and that we are here only to try to alleviate suffering. The field coordinator is also responsible for the internal management of the project, such as human resources for both expatriates and national staff, and also the overall logistics of the project.

So what qualities are needed for the role of field coordinator? Well, the main criterion is field experience. MSF would not send a person to work in this role unless they had already had some previous experience in this setting. Previous experience can come in the form of having done other, related work in the kinds of situations that a field coordinator works. For example, after I completed my degree in political science I worked for various non-governmental organisations. I worked in the field as a general administrator for finance and logistics: all this helped me towards my eventual role as field coordinator.

Although you have to face some tough mediation challenges, the rewards of successful negotiation are very satisfying. An example of this is a mission I was involved in in 2002 on the Pakistani/ Afghan border. After the fall of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan tens of thousands of Afghan refugees made their way across the border into Pakistan. But there came a point when the Pakistani authorities closed the border and simply refused entry to the 40,000 refugees still waiting to enter. They were also reluctant to allow aid organisations access to these refugees, on the pretext that they posed a security risk. After persistent lobbying, the Pakistani authorities finally allowed MSF to provide food distribution and healthcare. A humanitarian crisis was averted, and MSF would have been very vocal in publicising it. In the many volatile situations that MSF works in, there is the constant struggle to put the humanitarian effort first.

As an organisation committed to helping the needy regardless of their political or religious affiliation, MSF is committed also to broadening its human resources base. A lot of our work takes place in Muslim countries, I think Muslims working for MSF can sometimes have an advantage in this regard. Although it is against our ethos to have a model whereby we send Muslims only to Muslim countries, nevertheless we would like to encourage awareness amongst Muslims professionals that they could have a vital role to play in the global humanitarian effort.

Bookmark this |

|

Add to DIGG |

|

Add to del.icio.us |

|

Stumble this |

|

Share on Facebook |

|

Share this |

|

Send to a Friend |

|

Link to this |

|

Printer Friendly |

|

Print in plain text |

|

Comments

0 Comments