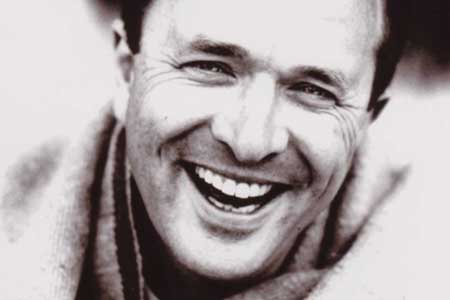

Meeting William Dalrymple

Issue 1 Sept / Oct 2003

White Mughals proved more than a scholarly journey for Dalrymple. He spent five years researching and writing the enthralling, tragic and fascinating love story. How does such an all-consuming exposition impact personally upon a writer? “I became obsessed with the story,” Dalrymple confesses. “I saw part of me in the main character, James Achilles Kirkpatrick. As I uncovered more details about the story I felt a greater affinity with the man. He and I had similar tendencies – our deep affection for India, our interest in Islam and the East.”

Writers are often asked whether their creations are thinly veiled elaborations of their own lives, however there was no question of Dalrymple blurring his own identity with that of his protagonist. “Kirkpatrick represented to me the choices I could have made but didn’t, the avenues I potentially could have walked down at various times in my life. He went much further than I have ever done in that I am not a Muslim and did not marry an Indian girl but these are all things I’ve hovered and hesitated over and could have done.”

The history of the British in India will never be the same after this book and neither will common assumptions about Islam. “The Islam of Mughal India was utterly separate from the stereotypes that prevail about this marvellous religion. Eighteenth century Mughal society, as lived in the book, is one in which women are formidable and sassy, forever running rings round the men.” According to Dalrymple, Islam during eighteenth century British India, “took on the colour of its surroundings.”

By introducing an entirely new poignancy to British rule in India, Dalrymple has broken new ground in the current debate about racism, colonialism and globalisation. As a historian who has spent many years researching and understanding British imperialism, I ask him whether he detects parallels with recent Western intervention in Afghanistan and Iraq. “Absolutely,” he declares without hesitation. “What we are seeing is in effect a re-visiting of the attitudes preceding nineteenth century colonial Britain. Now, as was the case then, there is a belief within the British and US governments that the people of the Muslim world are not capable of ruling themselves, that the so-called civilised nations of the West have every right to impose their will, because they’ve decided that is the way it is to be. This so-called War on Terror is barely disguised neo-imperialism, giving birth to oriental despotism as perfectly illustrated by the likes of Donald Rumsfeld.”

Dalrymple believes the events of September 11, 2001 provided the impetus for the US and UK’s current foreign policy, in much the same way as the Indian Mutiny of 1857 provoked a bloody and brutal retaliation from the ruling British forces. “With 9/11 and the Indian Mutiny of 1857, innocent people were killed. The response in 1857 was borne out of the belief that this terrible act, carried out by a minority of Indians, broke what were perceived to be the rules of war and therefore cast the entire Indian population as beyond these rules, beyond humanity.”

Similarly, in Dalrymple’s view, the events of September 11, 2001 re-wrote the rules of the global community and the West believed this horrific tragedy handed them the moral justification to redraw the political colours of the global map.

Dalrymple is unequivocal in his disdain. “The more I study the period of the eighteenth and nineteenth century, the more I am horrified by the parallels today. This is not liberal imperialism, it is neo-imperialism and every day the US steps closer and closer to this model.”

words: Samia Rahman

Bookmark this |

|

Add to DIGG |

|

Add to del.icio.us |

|

Stumble this |

|

Share on Facebook |

|

Share this |

|

Send to a Friend |

|

Link to this |

|

Printer Friendly |

|

Print in plain text |

|

Comments

1 Comment

1

Mehreen

6 Mar 11, 06:31

Very well-written! Yes history is merely just repeating

itself.