What Obama did not say

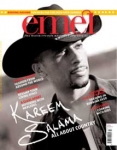

Issue 58 July 2009

The US president Barack Obama’s long awaited speech to “the Muslim world” was finally held last month, in the opulent surroundings of Cairo University. Critics pointed out two significant flaws with the location: that a speech with the lofty ambition of repairing America’s frayed relations with the Islamic worlds ought not to be held in an Arab capital, when the vast majority of the world’s Muslims live in Asia. And that, for a speech billed as a change from political business as usual, the capital of America’s staunchest Arab ally, with a dire human rights record, a long-serving president and billions of dollars in annual US aid, perhaps undercut the message.

Yet it was the message that mattered – and within the hundreds of words Obama spoke that night, there were some that were new, some that were very old, and much left unsaid

Start with the old. Some of what the US president said – about Islam’s role in creating the modern world, or acknowledging America’s role in overthrowing Iran’s democracy in the 1950s – is well-known, but in a way needed to be said by an American president. The odd thing about the legacy of the Bush years is that they made people believe that American politicians (as well as some British ones) could not see what was obvious to everyone else. So his words recognising the contribution of American Muslims or of the leadership of women in Islamic countries, which to some sounded like platitudes, needed to be said so that they were on the American political horizon.

Other platitudes came closer to eliding the truth. “I have made it clear to the Iraqi people that we pursue no bases, and no claim on their territory or resources,” he said. Yet the fact the largest US military base on the planet outside America is in Iraq, covering an area larger than Vatican City, suggests otherwise, as do the immense contracts given to US corporations like Halliburton.

On Iran too, he spoke of the acquisition of nuclear weapons, pointing out correctly that it would spark a nuclear arms race in the region, but without addressing why Iran – surrounded on two sides by occupying US troops – might be pursuing them. When he talked about religious tolerance, he invoked the divides between the Sunni and Shia Muslims in Iraq and between Maronites and Muslims in Lebanon – without mentioning that is the political context of war that has exacerbated those tensions.

But some of what Obama said was new. His words on Iraq as “a war of choice” were important to lay down a political marker. And on Palestine, he was clearer than many of predecessors, showing his understanding of the daily tragedies of the occupation, calling the situation “intolerable”, explicitly linking the Palestinian issue with American security and pledging America’s support for a Palestinian state. He was also as clear as it is possible to be on Israeli settlements, saying the United States did not accept their legitimacy and believed they should stop.

But there was much unsaid. In some places, he did not go far enough. On Guantanamo he reminded his audience that he would close the facility by 2010, but said nothing of the network of secret prisons around the world, nothing of coming clean on the involvement of foreign governments, nothing about opening the files of what actually happened at Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib, or of investigations into those involved.

And although there was a brief aside to Arab governments – including his host – not to use the Israeli-Palestinian conflict “to distract the people of Arab nations from other problems”, he did not push his hosts or other allies in the region enough on their own freedom deficits.

Obama was best on the issues that his sympathetic audiences in the West and the Islamic worlds could agree on: women’s rights, the importance of education and technological progress, the need for development. He went further than many expected, not as far as many hoped. And he did not address the context that allowed him, as the leader of one country, to speak on behalf of the West to the people of the vast Arab and Islamic lands. That context is that, for all the US president’s words and presentational gifts, America still has the military clout to act as it likes. That – if or when words fail – may be a difficult gift to give up.

Bookmark this |

|

Add to DIGG |

|

Add to del.icio.us |

|

Stumble this |

|

Share on Facebook |

|

Share this |

|

Send to a Friend |

|

Link to this |

|

Printer Friendly |

|

Print in plain text |

|

Comments

0 Comments