Craving a barbie body - All Dolled Up

Issue 66 March 2010

Only 1 in 100,000 women could attain Barbie’s vital statistics. With 1 in 100 women between 15 and 30 suffering from anorexia, Aisha Mirza, explores how the doll fits into the beauty myth.

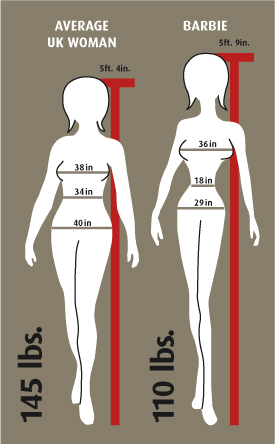

“I can be anything, from a rock star to a race-car driver, and so can you!” squeals Barbie as I visit her cyber walk-in-wardrobe. Unfortunately, it would seem that Barbie’s version of the American dream extends only to those who weigh 110lbs (7st 12lbs/50kg) or less. If Barbie were a human woman, she would stand tall at 5 feet 9 inches, rendering her size three feet quite inadequate for balance – especially when taking her F-cup breasts into consideration. Human Barbie’s waist would measure around 18 inches and she would lack the requisite 17-22% body fat required to menstruate, thus representing the body of 1 in 100,000 real women. When the figures are laid bare, it seems clear that Barbie’s physique is that of a plastic doll belonging to a fantasy world. But the truth is Barbie is very much a part of the real world too, and she symbolises generations of women who strive to be ‘beautiful’.

Courtney E Martin, author of ‘Perfect Girls, Starving Daughters’ writes, “Our bodies work on their own success/failure scale. We can work four years to get a degree, but can be failures in an instant once we step onto scales.” Such a sentiment will not be a surprise to women who have felt the inescapable pressure to be smoother, flatter, huskier, poutier and archier, and then the inevitable disappointment when their bodies don’t comply. From the corsets of times past that made fainting a predilection, to the Monolo pinkie toe amputations of today, women have a long history of enduring pain to be ‘beautiful’, and society has a long history of encouraging that. It is within this framework, where women are willing to lose dangerous amounts of weight and actual body parts in order to be validated as ‘beautiful’, that the potential danger of a Barbie doll becomes apparent.

In 1965, six years after Barbie was born, Mattel released ‘Sleepy Time Gal Barbie’ who was decked out in pink pajamas and eager for slumber party fun. Her sleep-over accessories consisted of scales pegged to 110lbs and a dieting handbook with one page of advice that read, “Don’t eat.” Barbie’s love interest, Ken, went to his slumber parties with cookies and milk.

Barbie has competition however, and it is not the “Islamic” Barbie spin-offs which are winning the day, but Bratz. With giant lips and erotic clothes, these ethnically diverse and arousing dolls have hit Barbie sales globally. The Bratz offshoot dolls, ‘Babyz’, takes the trend of sexualising pre-pubescent females to a whole new level by presenting actual baby versions of the dolls in a nappy, bra and make-up, with bottles of milk dangling from their necks and swinging by their thighs. Bratz also have a line of ‘bra-lettes’ -padded bras- which are currently providing ‘support’ for girls as young as six in Australia. Meanwhile, the hair removing product, ‘Nair’ has released ‘Nair Pretty’ with a target market of 10-15 year olds. Other additions to the girl product market have included Barbie Mac cosmetic range, Playboy Bunny Girl stationery available at WHSmith, Playboy Bunny Girl t-shirts available at supermarkets, a pole-dancing kit with the words “Unleash the sex kitten inside...” which Tesco had to remove from the toys and games section of its website following complaints. BHS also had to remove its padded bras and sexy knickers for the under 10s. Yet these small victories for the concerned consumer cannot halt the increasing sexualisation of children’s products by marketers who recognise the KGOY –Kids Growing Older Younger - market.

Where does all of this fit into an era that boasts of women’s liberation - a time that some even refer to as ‘post-feminist’? One thing we do know is that with the increase of women fulfilling roles of power and influence has come an increase in women ready to use that power to keep other women and girls enslaved in beauty rituals. In 1990 Naomi Wolf exploded onto the scene with her provocative and seminal ‘Beauty Myth’. She expressed much of the same dismay that Germaine Greer had, decades previous, stating that, “We are in the midst of a violent backlash to feminism that uses images of female beauty as a political weapon against women’s advancement: the beauty myth.” She explained that with a lack of role models in the real world, women seek them, “On the screen and the glossy pages.” In 2006 Ariel Levy wrote Female Chauvinist Pigs, to draw attention specifically to women’s roles in perpetuating this beauty myth. Given 81% of 10-year olds are afraid of being fat, when size-zero Kate Moss said, “Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels,” she was not simply irresponsible, she showed herself to be a Queen Pig. She and other women with influence who are choosing to take the place of more traditional chauvinists are not Barbies; they have flesh and brains, and taking that into consideration it becomes harder to know where to point our indignant fingers. But where women have power, they also have the power to make positive change.

Barbie celebrated her 50th birthday in 2009 and as part of the celebrations 500 dolls were made to represent different global cultures and auctioned at Sotheby’s to raise money for Save the Children. Among the dolls were one in a hijab and trousers and another in a vermilion green burqa. This decision prompted a predictable onslaught of anti-Islamic rhetoric, feminist outrage and ‘Taliban Ken’ style jokes, with the prestigious New York State National Organisation of Women (NOW) stating, “Women must be able to make their own choices… but the burqa is more than a choice. Women are forced to wear the burqa or risk being murdered… selling a doll that is clearly wearing a symbol of violence is not acceptable.” Whilst it is essential to draw attention to the human rights atrocities carried out against women in the name of Islam, calling for an unequivocal ban on the doll misses an important point. For the hundreds of women who are being hidden and abused under ‘Islamic’ dictatorship every day, there is a woman who is wearing her various levels of hijab/jilbab/niqab/burqa on London’s Oxford Street. For every feminist who believes that modest dress restrictions can be a personal choice but that they reinforce the misogynist ideal that puts a burden on some women to cover up rather than men to avert their gaze, there is a feminist who feels empowered by Islam and freedom in her modesty. She is a political actor, and just how feminist is it to dismiss her?

The phrase ‘Muslim feminist’ is often considered an oxymoron despite a plethora of literature which strives to prove otherwise. To be honest, if the news was my only portal into Islam, I too may assume that whenever feminism in Islam is mentioned, it must be ironic. However, I was raised by a woman who was empowered by a non-alcoholic cocktail of both feminism and Islam. I am forever thankful that it led to me being one of the least insecure and body-conscious young women I know. It’s not as simple as the donning of a hijab or the outlawing of Barbie dolls; it’s about relishing in the responsibility of being the primary example to the young girls around you, their first stop in the onslaught of socialisation that is to come. My mother’s decision not to have scales in our bathroom was revolutionary. Such acts are our ammunition in the fight for young minds and every woman has the power and dare I say it - the responsibility, to be an agent.

I still don’t know how much I weigh, but I am no Barbie. Unless my genes skip a generation, I don’t think my future daughter will resemble a Barbie either. Yet, would I buy her one if she asked? Absolutely! Whether she chooses one in a bikini or a burqa, it will probably end up wrapped in tin foil on a space mission, or if my child takes after me, naked and bald in the microwave. Regardless of what inspires women to fight against the negatives which society may expect of them, it’s the lifestyle changes real women stick by which ultimately influence our daughters – not plastic dolls. Empowering girls to love their bodies is not child’s play.

Cartoon Makeovers

Once upon a time there were cartoon characters you could rely on. They didn’t just shop; they discovered, they roamed space and rode around on their bicycles... Then came the marketers who decided they needed to be “revived for a new generation.” Suddenly the likes of Dora the Explorer, Rainbow Bright and Strawberry Shortcake went from cute, well covered little girls with dimples on their knees and freckles on their nose, to beauty queen wannabes with silky locks of hair, tiny waistlines and a whole new stylish wardrobe. Children of the eighties still had cute and cuddly role models. Today’s children are not so lucky; even the Care Bears and My Little Pony look as if they have been subjected to Trinny and Susannah fashion makeovers. It would seem when the marketers say “revived” what they actually mean is slimmed down and fashioned up.

<< Return to main article

This feature was first published in Issue 67 (March 2010)

Bookmark this |

|

Add to DIGG |

|

Add to del.icio.us |

|

Stumble this |

|

Share on Facebook |

|

Share this |

|

Send to a Friend |

|

Link to this |

|

Printer Friendly |

|

Print in plain text |

|

Comments

0 Comments