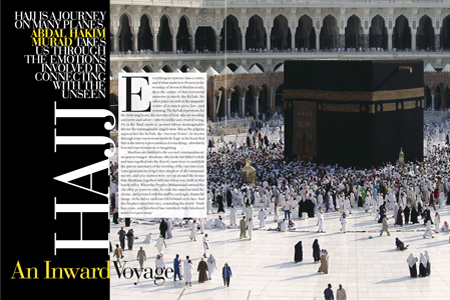

Hajj - An Inward Voyage

Issue 74 November 2010

Hajj is a journey on many planes, Abdal Hakim Murad takes us through the emotions involved in connecting with the unseen.

(This feature was first published in issue 51, December 2008)

Everything in existence has a centre; and if what matters to Heaven is the worship of devoted Muslim souls, then the centre of this terrestrial universe is surely the Ka’bah. No other place on earth is the magnetic centre of so much piety, love, and yearning. The Ka’bah represents, for the believing heart, the eternity of God, who we worship and serve and adore – utterly unlike any created being. He is the final mystery, around whose unimaginable throne the unimaginable angels turn. But as the pilgrim approaches the Ka’bah, the ‘Ancient House’, he knows through some mysterious symbolic logic in his heart that this is the truest representation of something – absolutely beyond representation or imagining.

Muslims are faithful to the second commandment: no graven images. Abraham, who broke his father’s idols and was expelled into the desert, came here to establish the purest sanctuary of the worship of the one true God. Later generations forgot this simplest of all commandments, and 300 statues were set up around the house that Abraham, together with his eldest son, built in this lonely valley. When the Prophet Muhammad entered the city after 30 years in exile, he rode his camel around the shrine, and pointed with his staff to each ugly, shameful image. As he did so, each one fell forward on its face. And the Prophet raised his voice, reminding the world: ‘Truth has come, and falsehood has vanished; truly falsehood must ever pass away.’

Muslims, privileged heirs of the purest monotheism, are honoured to bow towards the Ancient House five times in every day. The House thus becomes a great vortex of prayer. If one were to view this earth from above, with a light visible in the heart of every Muslim at prayer, one would see an endless series of luminous ripples and waves moving around the globe. As the people of the West are increasingly honoured by the presence of Islam, formerly dark regions are now filling up with points of light, as the absolute call of ‘No god but God’ is heard triumphantly in the spiritual ruins of materialistic cities. Five times a day and more, the Qibla draws our attention away from what matters so much less. ‘Allahu Akbar’, God is Greater, means: turn towards the symbol of His unknowable, unfathomable, majestic Unity and Beauty.

As the Muslim stands to pray, rising above and beyond those who are trapped in their own desires, he pushes behind him everything that has made him forget God’s power and scrutiny and mercy. Sleep facing the Qibla; never relieve yourself facing the Qibla, die facing the Qibla, lie in your grave on your right side, facing the Qibla, awaiting the final call, which will raise you to life, just as the Adhan raised you from spiritual death in the world.

Such a place is held in fear and awe. But in our Abrahamic religion, we move towards that place, through our fear and awe, to find love and stillness. Where the greatest crowds on earth come together, we find peace. The faces of those who have just returned from Hajj reawaken the desire for the House in all who see them. ‘And truly with hardship comes ease.’ Abraham is told this: ‘And announce the Hajj to mankind! They will come on foot, on every lean beast, from every narrow ravine.’ God commanded, and promised; and the Hajj shows how He honours His promises. The ‘valley without crops’ is sterile and austere, ringed by jagged peaks: Uqhuwana, Khandama, Thawr, Hira’. The culmination of Hajj, at Arafat, is the simplest and most ancient of rituals: simply standing ‘where tears fall and prayers rise’, with two million broken hearts. The beauty is in the rigorous ancient austerity of the rites, but also in the faces of a thousand races, all filled, as the sun sets, with the light of knowledge, and the hope for forgiveness.

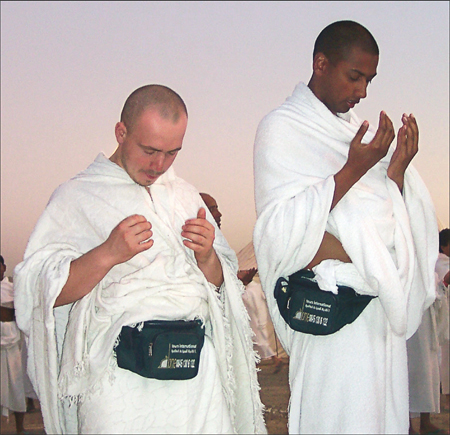

The City draws in these lovers of God each year, and then sends them home, like a heart pumping blood through the body. Most pilgrims have not come before, and as they approach, chanting the reply to God’s command to Abraham: ‘At Your service, here I am!’, their hearts begin to melt at the unfamiliar sights and rituals. Stripping away all their pretentiousness, they wind on the ihram, as though ready for the grave and its questioning angels. At once, memories long suppressed bubble up to the surface. The light of the Ka’bah makes us see our sins, and as we look within we are horrified by what we see. Forgetfulness, stupidity, laziness, cruelty, and more, in sins repeated year after year. Wrongs never put right, hearts still unhealed, come to mind painfully. The entry to the City is a time of fear, for there is no fear greater than that we might go to our graves unforgiven. The forms of Hajj must be obeyed; but acceptance is God’s alone and is not in our power.

‘Here I am’, and the pilgrim stands before the House of God. The mood of Madinah is Beauty (jamal); but the mood of Makkah is Rigour (jalal). The Ka’bah seems like an optical illusion, growing vast and majestic as one approaches, the eye disoriented by the velvet blackness of its coverings. Everyone seems to be talking – but the voices are of men and women engrossed in private prayer. While walking around the House, there are no set formulas, one speaks what comes to the heart. Qur’anic verses, prayers and litanies of the Holy Prophet, or words of contrition of one’s own devising: all may be heard. Some pilgrims are in tears. And at the most highly-charged place of all, the Multazam, beside the golden door, the atmosphere of hope, fear, love and yearning, cannot be described.

‘The accepted Hajj has no reward other than the Garden’, the hadith tells us. The Hajj is a purgation: uncomfortable and physically exhausting. Following the rules crushes the ego. Once round the Ka’bah can take an hour, but the pilgrim must circle it seven times. The crowds are immense, the heat staggering, the accommodation basic. Many who find a scrap of cardboard on which to sleep consider themselves fortunate. But at the end: a new birth, as the successful pilgrim ‘leaves his sins behind like a newborn child.’

Part of the spiritual power of the Hajj lies in its inculcation of wisdom. We may return to many of our ugly habits. But the memory of a sudden encounter with the ‘clear signs of God’, and of the power of repentance, stays with the pilgrim, as a reminder of the urgency of our need to remain pure of heart, and close to our Lord. Often, decades later, a memory of the Hajj can pull a sinful man or woman out of apparently hopeless vice. In that sense, the Hajj never comes to an end.

Bookmark this |

|

Add to DIGG |

|

Add to del.icio.us |

|

Stumble this |

|

Share on Facebook |

|

Share this |

|

Send to a Friend |

|

Link to this |

|

Printer Friendly |

|

Print in plain text |

|

Comments

0 Comments