Sailing towards the Divine

Issue 81 June 2011

Myriam Francois-Cerrah meets Ahmed Moustafa, the man whose works express eternal Truths from the Qur’an, just as the art of the Italian Renaissance masters expressed their belief in the Divine.

Photography by Henna Malik

The horse has long captured the imagination of writers and poets, who have often turned to its grace and audacity for inspiration. Islamic and pre-Islamic poetry is replete with references to our equine companion, whose stylised form adorns the banner outside the Fenoon Gallery in London. “Horses, amongst all animals, are the most significant creatures,” Ahmed Moustafa informs me. “The historian, Shaykh Yaqoubi, narrated in the traditions that God, after creating Adam, asked him to select any creature to be close to him. Adam chose the horse. God then said to him, you have selected glory for yourself and your offspring.”

‘Frolicking Horses’, 1993. Inspired by the poetry of Umro’Al Qaise, which mimics the sound of the horses galloping hooves in its rhythmic pattern. Oil and watercolour on handmade paper.

Ahmed is enthralled by the horse and its place within Arabic culture. One of his most breath-taking pieces, Frolicking Horses, is based on a pre-Islamic poem by Umro’Al Qaise, which mimics the sound of the horses’ galloping hooves in its rhythmic pattern and brilliantly captures the grace and power of the Arabian horse. Describing his objective in creating any piece of work, he says, “The way I perceive the creative side is a marriage between passion and enquiry into what makes any duality harmonious.”

Born in Alexandria in 1943, Ahmed was raised in the cosmopolitan city where historical influences from Pythagoras to the priests of Babylon forged a creative atmosphere. After studying fine arts at the city’s university, he was awarded the highest distinction in the history of modern Egypt, and received his graduation certificate from President Nasser himself in 1966. He was blissfully unaware of his natural talents until others began to take note. “I didn’t have a hand in being so gifted; it was entrusted to me by the Giver of Gifts — al Wahhab.” This modesty is an integral part of Ahmed’s spiritual outlook in which the objective is “to slay the ego” and not to allow the human desire to attribute success to the self, and in so doing, divert the focus of praise.

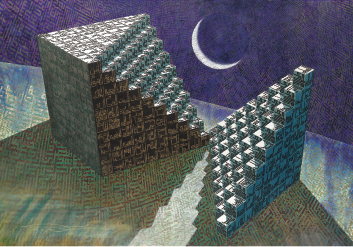

‘The Bedrock of Human Artistry’, 1998. Inspired by Qur’an 34:11, oil and watercolour on handmade paper.

Ahmed remembers an Alexandria where Italian, Greek and Egyptian painters all worked together. He describes the pervasiveness of Islamic idioms and references, which infused the culture of his youth as he pursued his studies in fine arts according to a western, occidental curriculum. “At that time, there was no course on Islamic art — or the art of Islam, as I like to call it. However, the environment was full of vocabulary associated with the art of Islam, whether in mosques, museums, books, the radio, costumes. The Arabic language is profuse with proverbs and sayings deeply rooted in Islam. It doesn’t matter if you’re a Christian; you still say insha-Allah because it is part of the common vocabulary.” Reflecting on this early period in which his Islamic identity was still dormant he comments, “I went through a period of my own jahiliyya; I’m not saying that proudly, but through that I was able to identify light, and without seeing the darkness of jahiliyya, I would not have known when the sun had risen.”

After being awarded a scholarship to study for a PhD, Ahmed came to England in 1973. At the Central St. Martin’s College he was challenged for the first time over the issue of his identity — and its absence in his work. This crucial encounter would mark a turning point in his own understanding of his calling and come to define a new direction for his work. “One’s destiny is something of a mystery; it was in England that I encountered for the first time the issue of Islamic art because of one question, which if I were in Egypt I would never have faced, and that was, ‘If this is your work, and this is your identity as an Egyptian, Arabic-speaker as well as a Muslim, where is its trace in your work?”

Overwhelmed by a question he had no answer to, Ahmed began a quest to resolve what he describes as “a state of crisis within me,” which made him turn to God. “I turned to the One who gave me this talent and I asked Him how to make this gift subservient to Him.” The answer came to him just before his return to Egypt, in a fortuitous encounter with Ibn Muqla’s work on Arabic script and its system of proportions. The discovery of an entire field dedicated to Arabic lettering launched him into the world of calligraphy and on the nature of the basic module residing at the heart of the system of proportions, the dot — al nuqta. The discovery of Islamic art led him to explore a new relationship with his art, an awareness that his own works were situated within a broader civilisational tradition bound by immutable laws and Divine principles. “The art of civilisation requires what you might call cosmic law — not the law of the ego. The ego of the artist is only trying to satisfy itself by any means possible, it doesn’t need any scientific support or logic of any kind. But when it comes to a whole civilisation, the artists’ ego perishes and he becomes subservient to the cosmic laws which govern that civilisation, and that is what happens in the art of Islam.”

More >

To enjoy the full feature in its entirety, pick up a copy of our latest issue. You can subscribe to emel here or give us a call on +44(0) 207 328 7300

Bookmark this |

|

Add to DIGG |

|

Add to del.icio.us |

|

Stumble this |

|

Share on Facebook |

|

Share this |

|

Send to a Friend |

|

Link to this |

|

Printer Friendly |

|

Print in plain text |

|

Comments

0 Comments