Hands of Clay

Issue 6 Jun / Jul 2004

First Published on July/August 2004

To access the issue page, click here

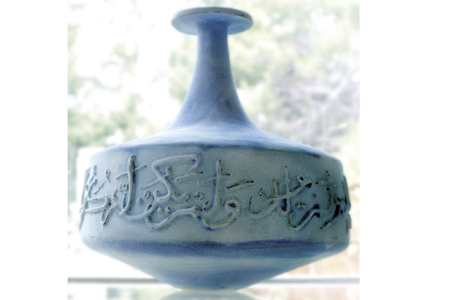

“It was when I first put my hands in clay, that was it.” Explains Parveen Zuberi. This is largely apparent considering that almost every walland shelf is adorned with boldly coloured ceramic plates, blue and white tiled pieces,tiny lidded bowls, heavy pots with obscure calligraphy in the kufic script, tall jugs and intricately painted dishes, all of which tastefully decorate her home. Her kitchen shelves aretidily cramped with bowls and serving plates,some are from China, others from Morocco and Spain. “Beauty should be part of everyday life and pottery is a pleasure to see as well asuse” she enthuses.

Ceramics have a deep rooted significance in the Islamic world. Not only were Muslims long ago evolving and perfecting the art of pottery, but also lending an influence to Easternart that is little known. For example, the familiar use of the colour combination of blue andwhite was utilised by Muslims centuries beforethe Chinese. Glazing techniques were continuously re-thought, white mane was developed in the 11th Century, the heyday of the Islamic ceramics world and in the 14th Century the Iranians developed the Sultanabad form.

Our affinity with pottery may stem from the Qur’an, where we are reminded of our own humble beginnings: ‘He has created man out of sounding clay. like pottery...’

It is not unusual for modern day ceramiciststo draw inspiration from Islamic pottery, asthe history of its development has been well preserved and is now vastly accessible. A reason for the Islamic mastery of the art has been suggested to be the prohibition of us in gold and silver vessels, so Muslims found an alternative in ceramic materials. The earliest Islamic involvement was when Arab Muslims manufactured a form of pottery known as lustreware in the 9th Century, and this spread with the expansion of Islam to the rest ofthe Middle East. Tin-glaze was also developed:a simple style not unlike porcelain that combined two clay materials, as well as the slip-painted method.

Originally well trained in glass painting, Muslim ceramicists had a vast impact onItalian works when they came into contact with each other at the latter stages of the Roman Empire. Muslim ceramicists have thusbeen attributed as some of the Fathers of the Renaissance, a time when art and painting rapidly developed in Italy.

Each age of a region’s history and technology adds a layer to the age-old tradition of Islamic ceramics. In Egypt the Islamic Ceramics Museum in Cairo harbours Egyptian pottery from each of the Fatimid, Ummayad, Ayyoubid, Mamluke and Turkish eras. The same can be said for other Arab countries,such as Kuwait and Syria. Here in London the Victoria and Albert Museum houses a vast array of Islamic ceramics, mostly inherited from the Empire.“

I wanted to keep up this tradition topass it on.” Parveen says. “It is not always consciously Islamic, one of my teachers at Watford College said to me that my work is very Eastern.” This statement rings true as I observe one of her early works - a shallow bowl with bright colours that seems meant to contain Middle Eastern food.

Parveen Zuberi’s education is altogether unusual for an artist, as she had originally planned on becoming a doctor. She was born in India, the fifth of eleven children, and was interested in the visuals from an early age. The family moved to Pakistan during Partition, where she studied science in Karachi and intended to continue to medicine. Instead, she was married to a doctor and moved to Britain in 1968. After her four children were born, she began a Visual Arts course in Ilkley College in Yorkshire, where she obtained a BA at Watford College which introduced her to ceramics, and eventually an MA at the Visual and Traditional Arts at the Prince’s Foundation.

The melding of science and art that Parveen Zuberi displays in her work comes easily to her. “They don’t have fixed boundaries, pottery contains a great deal of science, not least the art of geometry which was made alive for me by Professor Keith Critchlow at VITA while I was studying for my MA.” Critchlow is considered by Parveen as an expert in the field of geometry. One of his pieces is framed in her front room. “We did a swap. He took one of my pieces, and I took one of his.”

Upon leaving formal education Parveen’s abilities were continuously excercised by her hobbies of silk painting, embroidery, calligraphy and painting on canvas. When her husband retired he bought her an electric kiln and wheel as a gift, now set up in her workshop where shelves display various stages of nearly-finished works, some containing only white bowls that need painting, others with almost finished examples.

“It is very physical work. My daily routine is to do the housework, read Qur’an and tidy up until eleven in the morning, and then I get started. Sometimes I don’t want to break for dinner, I’m so engrossed. It takes weeks to finish a piece, and the process is laborious but when you are firing up the kiln and the pottery goes in, all the four elements are working; earth, fire, wind and water.”

Bookmark this |

|

Add to DIGG |

|

Add to del.icio.us |

|

Stumble this |

|

Share on Facebook |

|

Share this |

|

Send to a Friend |

|

Link to this |

|

Printer Friendly |

|

Print in plain text |

|

Comments

0 Comments