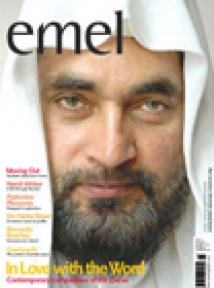

An Attendant in a Human Drama

Issue 7 Sept / Oct 2004

Dr Amina Coxon's colonial upbringing betrays little sign of her interest in Islam. An eminent Harley Street neurosurgeon with extensive experience of hospital medicine and General Practice, she has also contributed to a research project in Holloway prison on human violence. Here, in conversation with Samia Rahman, she reflects upon her experiences as an unlikely convert negotiating the psychological and spiritual processes of life.

There is always a psychological dimension to conversion, believes Amina Coxon. Her window to the world of Islam slid ajar as a young girl - she was initially brought up in America but aged fi ve years old at the end of the second world war she travelled to Cairo to join her father where he was working in the cigarette industry, “So I was from a very early age familiar with Islam, growing up in an Islamic environment with the staff praying and hearing the call to prayer which I loved.” Islam was intertwined in her childhood, “the background noise of Islam was normal for me,” but it also carried many deeply negative connotations. “After two attempted kidnappings I was shipped off to boarding school in England. During that era, holding colonial children hostage reached a good price.”

The drama of failed abductions remains a vivid memory for Amina, “I remember both kidnap attempts - each time I was in a taxi with my brother who is fi ve years older and was 11 at the time. Both times the taxi started travelling in the wrong direction and my brother immediately knew what was happening and waited for an opportunistic moment for us to jump out of the moving car. I was screaming, it was very dramatic.” Violence and danger punctuated Amina’s early years, “our school bus was held up one time and another particularly unpleasant incident occurred when a child was found with human bite marks all over his body and had evidently been bitten to death.” Such was the hatred and anger felt by the Egyptians towards the colonials. “So I didn’t necessarily think of Muslims as nice people but having said that I didn’t think of them as Muslims - I thought of them as Egyptians. They harboured deep resentment towards colonials.” Amina and her family often took extraordinary measures to protect their lives, “We lived on the island in the middle of the Nile called Gezira, which was safe in case of riots.

On this occasion we were in central Cairo getting our hair done and I said I can hear bumble bees and the hairdresser made everyone be quiet and sure enough you could hear brrrrrrrr. The woman freaked and everyone fl ed into the road with curlers in their hair and towels around their neck. As we had nowhere to go my mother put each of us in a laundry basket with a whole load of dirty linen on our head and we hid in a cupboard. She said whatever happens do not make a sound and I knew that this was serious. I heard broken glass, a lot of shouting, but fortunately nobody came near the laundry baskets.” It turned out there had been a devastating riot. “During another riot, an English club was set on fi re and the people trapped inside had the horrifi c option of either dying in the fi re or jumping out of the windows and being hacked to death by the crowd. This was known as the Turf Club fi re and is well-known in colonial history. We lost many of our friends in that fire.”

I wonder at the impact such a perilous childhood must have had, “Children get accustomed to anything so to me it was normal to live amidst such turbulence.” She explains that it was her forced removal to England that was far more traumatic. “What affected me more was moving to a strange country and going to a boarding school and having to spend holidays with strangers because my parents couldn’t come over except during the summer holidays.

At all other times I would have to find people to stay with.” Feelings of rejection and hurt inform her memories. “It was difficult. I know I’m psychologically affected by it because although that teaches you independence and resourcefulness which are good things to have, it also teaches you a deep distrust which is inappropriate especially when the basis of intimacy is trust.”

Audemars Piguet Replica Watches

For Amina, the detachment of her parents inflicted an emotional wound that still resonates, “My father was working and my mother chose to stay with him rather than send for me or come to England to stay with me. Once a teacher found me crying at the end of the summer term and asked me what the matter was. I said that I was worried about going on the train to Victoria and she asked why, wasn’t someone meeting me there? I told her my mother was but that I don’t know what she looks like. The teacher comforted me and said, ‘Well you’re the only one with red hair and your mother will recognise you.’ I was worried that I was going to be standing on Victoria station, nobody would claim me and I wouldn’t know what she looked like so I wouldn’t know who to walk up to. It is curious when I look back at how normal that was to me at the time. Children accept it because they don’t see the things that are happening to them as anything other than normal.”

Amina had an appropriate psychological reaction to her situation. “I was quite delinquent and was soon expelled from the first two schools I attended for being impossible to handle. I would set off an alarm clock in the middle of a church service and release a mouse in the chemistry lab.”

There is little doubt that this was the behaviour of someone crying out for attention, however her experiences at her third school marked a turning point. “I had arrived in the summer term which was already rather awkward and I started as I intended to go on - breaking every rule and had made my mark as somebody who couldn’t be tamed.” By the end of the term Amina braced herself for a scathing end-of-term report from the headmistress. To her astonishment, “She went on and on about my scholastic skills in great detail and wrote only one line about my behaviour: Ann has a tendency to exhibitionism which she will control when she wishes.” The school’s accept- ance proved to be very good psychology, “from that moment I was the model student.”

Amina eventually became Head girl, “I was one of those nauseating girls who was in everything and because I have a low voice I was in lots of singing performances and I received many prizes for this,” but her achievements went unheeded by her mother and father who had, “long since given up on me so much so that they didn’t even read my reports or knew what I was studying. I was aware there was no point trying to impress them with anything, they just didn’t notice. They had no expectations of me and I realised that whatever I would do in my life would be my own journey.”

Amina’s career path involved a series of spurious decisions. “There was a critical point at fourth form when you have to decide whether to do sciences or arts. It was announced from the stage that all those in the fourth form doing arts should go to the left of the room and all those doing science should go to the right. My worst enemy, who I was very jealous of, was a very bright diplomat’s daughter: she went to the arts and I thought I’m not sitting next to her for another two years so I went to the sciences. Not exactly what one calls deep thought! Then a former pupil who was a doctor visited the school and everyone said isn’t she wonderful she’s a doctor so I thought I want people to say I’m wonderful and that is the reason I became a doctor!”

When Amina qualified in medicine there were no European directives regarding the hours a junior doctor worked, “In the first year I had two week- ends and ten evenings off so it was tough but it was fantastic training.” She felt the gruelling schedule was necessary, “I don’t think junior doctors now get the same amount of experience. It was exhausting, certainly, and so we took uppers. You could steal products from pharmacies, we all did, to keep you going. If you were up all night on an emergency and just didn’t get to bed, you had another day to do and then if you were up the following night too it became impossible to function but I was very well trained and I loved my career because I think I trained at the best of times.” Characteristically striving for perfection, Amina as a student at Guy’s, famously diagnosed a case of tertiary neurosyphilis in defiance of the senior Physician. She opines the bleak life of a newly graduated doctor to be a vital education. “It is a lot easier now for junior doctors which of course is good for them but I don’t think they’re getting the clinical experience they need to become good doctors. They are not seeing enough.” Amina left the National Health Service in 1983, “I thought my ability to practice good quality medicine was being compromised.”

A successful career as a neurologist may inspire delusions of grandeur in some but not so in Amina, “You are humbled by the courage of your patients, you are humbled by your ignorance, by what you can’t do.” She describes her role as, “an attendant in a human drama,” and provides an insight into the inevitably taut tension of the practitioner, “If a surgeon loses a patient they will feel crushed because they know somewhere in the world exists a surgeon who could have helped that patient. At every point doctors are left with a knife in the gut, reflecting on what they might have done better. That is why we have a defensive arrogance coupled with one of the highest suicide rates of any profession. You have to do your absolute level best and then give the rest to God.

That is why bismillah (in the name of God) is my favourite saying and I am constantly saying it, asking to be protected from things I might do wrong and to protect my patients.

Where her professional career was faultless, Amina’s personal life was the cause of much pain, “I made the same mistake twice. I married two men who in different ways needed me rather than understanding the larger dimension of a partner- ship.” The anguish of abandonment she endured since childhood manifested itself, “I wouldn’t count that part of my life as something I would do many re-runs of. When I look back with the wisdom of hindsight I realise I made a very fundamental psychological mistake twice. I couldn’t believe anyone wanted me for me so I had to be needed. Once you fulfil somebody’s need they don’t want you any- more.” Since embracing Islam Amina admits to vaguely wondering how things would have turned out had she married a Muslim. “When I look at other people’s happy marriages I feel enormously happy for them and then I think wouldn’t that have been nice but it is like someone who is tone deaf listening to Pavarotti and saying wouldn’t it be nice to sing like that. There was a big gap between the person I was, the choices I made and the reasons I made them and the maturity of the people whose marriages I am in awe of.”

Amina’s own journey to Islam evolved inadvertently as she strove to understand her fraught familial and marital relationships. She had been a fervent Catholic from a very young age. “For a child as deprived of human parental contact as I was, religion became an absolute natural haven. I became an extremely passionate Catholic and I found the mysticism of religion absolutely fascinating.” Her enthusiasm was voracious, “I had a book in which if there was a Saints Day it gave you all the details about the Saints’ life and even more interestingly the Saints’ death. I became an expert on which Saints had been boiled in oil, which ones had had their skin stripped off, which ones had been crucified upside down and so on. I was completely ghoully. I wasn’t particularly interested in their lives but I knew every torture in the book.” Amina’s unique appreciation of faith at that age was unremarkable to her parents, “neither of whom went to Church – my mother’s idea of religion was ‘great it’s Friday we can eat smoked salmon and oysters’ (Catholics aren’t allowed to eat meat on Fridays).” But her Great-Aunt who was a nun at the school encouraged her to explore religion beyond the deaths of Saints, “She wasn’t impressed with my spirituality.”

The adherence to Catholicism matured with the advancement of years as did her understanding of the complexities of faith, “I took religion seriously even after I had left school. I was a regular church- goer and the concept of a deep connection with another dimension was important to me.” After the tumult of her marriages, Amina felt she needed to venture further, “I asked for more in terms of my religion. My limitations as a person were painful to me and I searched for an explanation or meaning to who I was. My character is stubborn and I was constantly saying to God ‘I know there’s more. I know if I keep knocking and saying you’ve got to show me, you will!’ I had no idea that what I was going to be shown was the path to Islam.”

Converting to Islam may have been the last thing on her mind, but Amina’s path was beginning to clear, at least on a subconscious level. “I was always impressed by the faith of Muslims in the face of adversity. On one occasion I was treating an elderly lady who was due to have an operation. I also examined her daughter and discovered she had breast cancer which was at a very advanced stage. I explained the gravity of the situation to the family and emphasised that she must be told. To my surprise, the next day I found the family laughing and joking. I was furious, assuming they hadn’t told her that she was seriously ill. But in fact it turned out that they had and instead of being devastated by the news she had spent the entire night praising Allah and giving thanks that her cancer had been detected. I was astounded by the strength she drew from Islam.”

It was also her close friendship with the mother of the Sultan of Oman, who she describes as, “the strongest woman I’ve ever met,” that accentuated Amina’s path. “I was struck by her compassion and understanding. When she was ill she carried on with her hectic daily programme which made me angry as I felt she was putting herself at risk.” On one occasion she remonstrated to her friend and patient, “‘You give to everyone. Who gives to you?’ to which she fervently responded, ‘Allah.’” This proved a defining moment for Amina, but it was not until a vivid dream came to her one night that she felt her destiny become re-aligned. “I was driving across London on a single road and saw flames shooting out of houses and rocks falling on to my car. I then seemed to be driving over a bridge and into a desert before seeing a dazzling light ahead of me within which was the name of Allah. I thought this was a message that my path was Islam.” She converted two years later in March 1990.

Having always been fascinated by the human personality, Amina engages her knowledge of the physical dimension of the brain with psychoanalysis and spirituality. “I am very interested in this triangle and coming from an interfaith angle I found that Islam is not so different to other religions. A person who has a spiritual dimension realises they are an empty shell, a vehicle to either transmit Allah or transmit Shaitan.” But she laments the inherent racism within the Muslim community, “There isn’t one ummah. When I was a Catholic I would enter a cathedral and on one bench there would be ten different nationalities and we would all hug one another. You feel yourself part of that universality of religion and the only time I have felt this since becoming a Muslim is when on pilgrimage.” She also laments the divisive effect of blurring culture and religion, “there is an immense cultural specificity which forms a cultural identity that involves immigrant communities in Britain labelling themselves proudly as Muslims while also turning this label against themselves. This image becomes exclusive, arrogant and even violent.” However, she is optimistic that, “a great hope lies in the new generation.”

Amina was featured in the first BBC documentary of Hajj and has since been inevitably quizzed about the status of women in Islam. “Men reinforce one another. That is the situation in all communities; however I am not in the least in despair of women’s place in Islam.” She calls on Muslim women to make intelligent choices, “as a Muslim woman in the West, many opportunities are available to us. In order to keep these options open, the first step is to be careful who you marry. If you have a supportive and non-threatened husband, he will encourage you to fulfil your potential but unfortunately many Muslim men are weak and the wives find themselves falling into a protective co-dependency.” With co-operative families and the demarcation of traditional social boundaries Muslim women will have a great deal to contribute to their communities and beyond, “Muslim women need husbands who have the confidence to say ‘I’ll stay at home and baby-sit tonight so you can go to the meeting.’” Marriage becomes a team effort with each partner supporting the other’s aspirations and goals. “Many marriages work because the man is intensely proud of his wife’s capabilities and acknowledges her need to express her talents.”

Amina’s embrace of Islam has not been without its challenges. 9/11 forced her to confront a dimension she felt to be alien to her understanding of the religion, “My brother lives in New York and when I heard that my young niece had been coughing as a result of the fumes from the burning twin towers I felt ashamed.” She offers her perspective, “To me it is a tragedy that people politicise religion,” and implores all members of the community to take responsibility. “Moderates have to stand up and be accountable. The danger arises when jihadis practice their poison without opposition.”

Amina has her own thoughts on how the Muslim community in the UK can protect their interests and counter the extremists, “Muslims in this country should vote. Only by being informed and taking part in the political process can we assert our rights, not by bombing and screaming and fighting.” The Muslim community also needs to establish itself in order to live in harmony in Britain. “It is unhelpful when immigrant Muslims come to the UK only to restrict themselves to their ethnic groups and not involve themselves with the goings on of the wider community. What is even more maddening is when they sit back and criticise.” According to Amina, this insularity serves to detach Muslims from non-Muslims, feeding mutual suspicion and tension.

Amina has suffered serious illness this past year but remains philosophical. “Being sick is a blessing. It makes you focus on what life is actually about because your material possessions come to mean nothing. All you have is the mercy of Allah and the opportunity to represent yourself and show how you have reverenced Him.” Now she is recovering she has sought to nurture her spiritual path by deepening her understanding of Islam and Allah’s Will for her. “It didn’t occur to me to question ‘why me?’ If there is one lesson I have learned in life, it is not to rage against your destiny. Everyone has a purpose that is known to Allah.”

Bookmark this |

|

Add to DIGG |

|

Add to del.icio.us |

|

Stumble this |

|

Share on Facebook |

|

Share this |

|

Send to a Friend |

|

Link to this |

|

Printer Friendly |

|

Print in plain text |

|

Comments

0 Comments