In the Director's Chair

Issue 7 Sept / Oct 2004

Navid Akhtar is an independent radio and television producer, director and broadcast journalist. He has made documentary films for the BBC on ‘Islam in Britain’ and the ‘Islam Season’ in 2001. He also directed ‘Ramadan Diaries’ for Channel 4 in 2001 and was a producer for its Hajj series ‘Trip of a lifetime’ screened in Feb 2003. His Radio 4 documentary ‘Blood Feuds’ received the Prix Europa 2002 Jury Special Commendation for Radio Current Affairs and he recently produced a one hour biography on Cat Stevens - Faith and Music, for ITV.

It was a real honour to work on two films about Hajj, one for the BBC in 2001 and then for Channel 4 in 2003. It was hard going to Hajj and not being able to perform it but I spoke to my friends the photographer Peter Sanders and film maker Abdul Latif Salazar who both told me that Hajj should be made with clear intention and not when working. So I hope I get some reward for just doing a good job.

Navid Akhtar is an independent radio and television producer, director and broadcast journalist. He has made documentary films for the BBC, on Islam in Britain and the Islam Season in 2001. He also directed Ramadan Diaries for Channel 4 in 2001 and was a producer for its Hajj series, Trip of a lifetime screened in Feb 2003. His Radio 4 documentary Blood Feuds received the Prix Europa 2002 Jury Special Commendation for Radio Current Affairs and he recently produced a one hour biography on Cat Stevens Faith and Music, for ITV.

Every day”, exclaims Navid Akhtar, “I think about who I am.” He feels he has lived his life always in the middle. Between elder siblings, who are very Pakistani, and younger ones who feel more British. Between the strict Muslims and those who don’t practice. Between his urban London life and the rural tribal values of his family. “Life in the middle is not easy, but you do learn to see things from all sides and it seems at times that my whole life is about explaining the view from the other side.” It has also given him a rich identity that is a hybrid of Muslim/ Kashmiri and Londoner.

Like most first generation Kashmiris, Navid’s father had a strong work ethic, “He was a chef and he worked in some of London’s finest Indian restaurants,” and high expectations for his children. “He would say to me, ‘I have to stand to earn my living. I want you to sit at a desk to earn yours.’” His mother was also instrumental in nurturing his aspirations. “Everything was geared towards making sure we would grow up to be good people and have a better life. From a very early age she was convinced that I would go far and having that constant positive mantra had such an effect on me. I pass that on to my daughter now – total unconditional belief and love. I could say to you I know what it feels to be cherished, to be loved like that. It is an incredible feeling. Important to your sense of who you are and gives you incredible confidence to go out and do things.” His mother’s belief would eventually come to fruition - Navid won the Muslim News Ibn Battuta Award for Excellence in Media in 2002.

Navid describes himself as, “absolutely the TV generation, my earliest memoriesare of watching television. It also educated me immensely. There’sstuff I would have never known about - we watched endless hours of documentaries and travel programmes.”At school Navid discovered a talent for graphic art and embarked uponan Art Foundation course. His mother’s response was, “don’t tell your father.Say its architecture or something.” He then went on to the London College of Furniture to study interior design where he, “met these hippyteachers who made me realise that I actually came from a wonderful culturethat wasn’t just about Bollywood films and curry. I absorbed myself in Mughal and Islamic architecture. I was part of the generation that was interested in cultural fusion – bringing together those two aspects of ouridentity, Pakistani and British.

”Navid wrote his BA dissertation on Victorian Design, William Morrisand the Raphaelite movement, “a thoroughly English subject but I couldclearly see the influence of Islam.” Very little work had been done in thisarea and his tutors gave him a first. He went on to work on a project called ‘Pakistan and Its People’ for schools television. “I assisted a crewfor two six-week stints in Pakistan. It gave me a taste and I thought Icould do this. Much of it was about being diplomatic and convincing people to co-operate.” He then went to work with Tariq Ali’s companyBandung making short films. “It was a very small company and I wasthrown in at the deep end but I had the enthusiasm, learnt loads anddidn’t really look back after that.” Getting a job at the BBC only cameafter five attempts, “each time I would be interviewed by an intimidatingpanel firing questions at me.”Navid quickly confounded stereotypes at the BBC, “I had an understandingof Pakistani and Islamic culture but I also knew about contemporarydesign and 20th century architecture so I had other strings to mybow and never solely relied on ghetto subjects."...

his experiences therefore proved eclectic, “I did a series of Home Front which I thoroughly enjoyed and people were impressed by my encyclopaedic knowledge of design.” It wasn’t long before he entered into the documentary arena and firmly found his footing, “There I met Janice Hadlow who was an excellent mentor and is now controller of BBC4. Janice set up the history unit and I was hired on a project researching the life of the Shah. She never patronised me and she had a belief that I could do anything, I even ended up doing a film on opera and I would be blank faced thinking why me? I worked on all sorts of subjects that broadened my wealth of experience.” Navid travelled to Japan and made a film about the Samurai, “which next to the Hajj is my most favourite programme – I met some amazing people. It was a real honour to work on two films about Hajj, one for the BBC in 2001 and then for Channel 4 in 2003. It was hard going to Hajj and not being able to perform it but I spoke to my friends the photographer Peter Sanders and film maker Abdul Latif Salazar who both told me that Hajj should be made with clear intention and not when working. So I hope I get some reward for just doing a good job.”

Life was drawing an upward angle until the death of Navid’s mother in 1996 which affected him deeply. “There is an emotional side to me which means it is very difficult to be upset for two weeks and then go back to work. Asian Muslims come from complex families where life is all about responsibilities. As much independence as you gain, as much as you feel you’ve struck out in the world and made your mark you can’t ignore that side of your identity.” This is illustrated by his father’s recent illness, “It is a difficult situation to reconcile because my career is com- promised but either I put him in a home or I look after him.” Navid concedes his story is not untypical within the Muslim community. “I come from a culture where if somebody dies 400 miles away, I am expected to leave work that afternoon, get in a car and drive up there to pay my respects.” This is where he and his non-Muslim colleagues differ. “We’re under different types of pressures. There is no imperative for me to do such things, but it makes you who you are. Maybe my daughter won’t do that, I don’t know – maybe when I’m old I’ll be saying to her ‘put me in a home – enjoy your life.’”

The media is a creative industry and the danger is that, devoid of spiritual depth, you can easily burn out. “You have to have space and time to renew that sense of who you are. My mother’s death interrupted a life of fairly constant living and I experienced a shift towards a more conscious practice of Islam, a desire to absorb it deeper.” His re-appraisal of faith coincided with a series of emotional experiences, “I became a father and subsequently was divorced. It has taken me a while to rein all that in. My faith has helped me make sense of it all.”

Navid is realistic about the representation of Muslims in the media, “We are an eclectic, diverse bunch and for a white middle class producer it is difficult to get a handle on that and then put it out on a programme for the average TV viewer. I am personally interested in reaching a wide audience – public broadcasting – and for this reason I will not work for an Islamic channel on principle because to me the value in the work is to connect with wider society. I often feel manipulated by the expectations of the Muslim community who aren’t willing to face up to shortcomings.” His view is that the community need to develop a sophisticated understanding of the media. “Do we want programmes that just make Muslims happy?”

He advocates programmes which, “break down stereotypes and show the diversity of Islam without getting bogged down in obscure arguments and inverted ideas. What is being left out is the immense wealth of cultural history, ideas and civilisation. It would be a dream to make a programme about Islamic gardens or architecture instead of the usual ‘what’s wrong with Muslims’ angst.”

For Navid there are disappointingly few Muslims breaking into the media because, “many youngsters have written it off, but,” he continues, “they need to recognise you can have a spiritual belief and be engaged with the world. Your Islamic identity will inform your work but it has to come with skills and experience. I hope we can have more film makers who happen to be Muslim, and not amateur do-gooders.” He believes that it takes time to learn and produce work of quality, “having struggled to smash through the glass ceiling, I am going to do all that I can to try and make sure it doesn’t turn into a glass cliff.”

words Samia Rahman

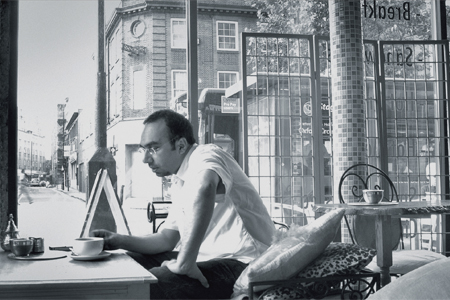

photo Omair Barkatulla

Bookmark this |

|

Add to DIGG |

|

Add to del.icio.us |

|

Stumble this |

|

Share on Facebook |

|

Share this |

|

Send to a Friend |

|

Link to this |

|

Printer Friendly |

|

Print in plain text |

|

Comments

0 Comments