The Talented Mr Gai Eaton

Issue 1 Sept / Oct 2003

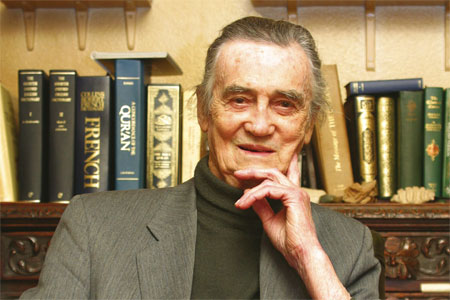

Samia Rahman meets writer and scholar Charles LeGai Eaton to reflect upon life, spirituality and the tumult of our times.

As I enter Charles LeGai Eaton’s quintessentially colonial gentleman’s home, a bold, curvaceous 1960sstyle CD-playing jukebox catches my eye. Unashamedly retro, it stands out in a room steeped in the marvels of history, a room which is a reflection of the man himself; infused with memories of long ago and immersed in a sense of spiritual purpose and the accumulation of knowledge. I comment on the time-honoured sea shells adorning the mantelpiece and learn they are a memento from a holiday taken long ago with his young family in Burma. I wonder what secrets they whisper from the bottom of the Bay of Bengal.

Eaton has directly experienced many significant global events of the 20th Century and, although his 82 years do not betray him, there is a vulnerability in his manner as he manoeuvres across the room to pour himself a glass of water. His frustration at the stroke he suffered nearly two years ago is evident. “I never had a problem with my health until then,” he explains, “now I take each day at a time.” Born in Switzerland and educated at Charterhouse and King's College, Cambridge, Eaton worked for many years as a teacher and journalist in Jamaica and Egypt, where he embraced Islam in 1951, before joining the British DiplomaticService. He is now consultant to the Islamic Cultural Centre in London and has written and published many books about the spiritual, historical and political nuances of Islam.

It is the turmoil of world history that has concerned Eaton ever since he was a small boy. In Islam & The Destiny of Man he describes himself as having been, ‘not an average child,’ and still treasures the innocent wonder of a young mind. His reverence for children leads him to believe that, “some children are born with metaphysical curiosity… that curiosity was why I later took an interest in philosophy.” Adults often have difficulty appreciating this quality in children, “it is soon snuffed out of them,” according to Eaton. “Average children may have more to them than appears, if they were respected.”

To illustrate this point, Eaton recalls an incident that affected him profoundly as a child. He was 12 or 13 and just becoming consumed by world affairs. Upon learning that the Austrian Chancellor had been assas- sinated by the Nazis, he remembers weeping over this sombre incident. When Italy subsequently invaded Ethiopia, employing napalm for the first time in warfare to cause maximum death and destruction, the international community refused to interfere. In fact, the British Foreign Secretary, Sir Samuel Hoare conspired with the French to persuade a weakened League of Nations to sign the Hoare-Laval pact, allowing Mussolini to ravage what was then called Abyssinia.

It was at this time that a “sense of justice” possessed Eaton and he became hugely angry. But how does a child express that anger – nobody listens? Around this time, Harrods had installed a small recording booth, and was inviting children to enjoy the thrill of hearing their own voices recorded. Other excited children sent happy messages to mummy and daddy, but Eaton went into the booth blazing with fury and savagely renounced Hoare and Laval as wicked men, wishing them every ill possible. His wish came true, as at the end of the war, Laval was hanged and Hoare disgraced. It does not escape me that this story has deep parallels with current global events. I ask Eaton what his feelings about the recent war in Iraq are and it quickly becomes apparent that he is not afraid to ride against the majority view. He is, over “the Saddam business,” as he calls it, “very torn”. Eaton points to the lack of proof that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction, to coin a very 21st Century phrase, and refutes any likely link between the deposed Iraqi regime and Al Qaeda.

However, he is ambivalent about the course of action taken by the US and UK. “Saddam was such a monster. To an extent, just as I feel we should have interfered in Ethiopia, maybe we were right to interfere in this case. I am very torn either way and I cannot quite make up my mind what I think.” Such a controversial statement by a highly- respected and influential Muslim figure has a deeper resonance and I sense that, in his despair at Saddam, Eaton despairs at the state of the Muslim world, which he vehemently feels should address the issue of tyrants, injustice, poverty and human rights abuses littering its own back yard instead of turning a blind eye to people like Saddam, “He was our monster, it should have been for us to deal with him.”

Despite conceding that he may be idealistic or over-optimistic in his expectations, Eaton is unequivocal in his frustration that the Muslim world, which once warranted the title the ‘cradle of civilisation’, has crumbled into a smouldering hot-bed of ineffectuality and division. Seeming to shirk obligations, Muslims have even become distracted by the notion of national sovereignty which Eaton refers to as the “sacred cow” of the West and which has no place in Islam. “If the ummah (global community) of Islam was in any sense united, then we would have dealt with Saddam because the Qur’an condemns oppression, condemns oppressors, and it would be the duty of the community of Islam to force people like that out of power.” According to Eaton, “we are so hopeless and helpless we leave it to other people who have their own motives and their own objectives.”

So what is the problem with Muslims? What can we do to remedy the current malaise? Eaton directs a weary look at me as if to indicate this is not the first time he has been confronted with this question. “That’s the $64,000 question isn’t it? And there are no easy answers. The Qur’an reminds us constantly of the rise and fall of empires and nations and tribes and peoples. We reached a certain height from a worldly point of view, not necessarily a spiritual point of view, and we have declined. In the 17th Century the West out-distanced us due to industrial developments and, for a people who had once been on top this was a shocking experience - we were reduced to subordination, some of us were reduced to a colonial situation and it takes some while to get over that. The wound or the humiliation takes an awfully long time to heal.”

It occurs to me this train of thought could give some weight to the Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington’s much-discussed theory. In 1993 Huntington published The Clash of Civilisations and the Remaking of World Order, simplistically declaring that civilisations were differentiated from each other by religion, history, language and tradition. From Yugoslavia to the Middle East to Central Asia, he predicted the fault lines of civilisations that would become the battle lines of the future, and encouraged the United States to forge alliances with similar cultures and spread its values wherever possible. With alien civilisations, according to his theory, the West must be accommodating if possible, but confrontational if necessary. Eaton does not apologise for inferring the connection, “I think there is bound to be a clash – the values of Muslims are in such contrast to modern Western values - the degeneration that has taken place throughout my lifetime, that opposition is inevitable.” Eaton is aware he may be accused of being disapproving and out-of-touch with the times but as he readily admits, The Richest Vein, written while he was still in his twenties, encapsulated the same disapproving voice: “At least I understand more now and perhaps I am more tolerant, but at 25 I thought I was living in the most degenerate age ever.”

Eaton is held by the Muslim community in great esteem as an Islamic scholar and consultant in religious matters. He is also a spiritual icon. His talks are enthusiastically attended and his opinion deeply respected. Yet his strictly agnostic upbringing was hardly a grounding for a lifetime of religious exploration. “I can still remember my puzzlement when I was seven and I went to stay with a friend. When bedtime came the little girl kneeled down and prayed. I had no idea what she was doing. I asked my mother. She told me she was praying to God, and I replied, but what is God? It was a very strange idea to me indeed.”

So, how does Eaton explain his journey from a very unbelieving childhood to embracing Islam in his late 20s? His mother was determined her son would not have religion crammed down his throat, yet he, “needed to know, it is as simple as that.” This metaphysical curiosity lead him to engage with philosophy at the age of 15, but he was disappointed by the likes of Heidegger, Nietzche, Kant and Hegel, “because they didn’t know. They were speculating. Since my mother told me never to take any notice of what anybody thought or believed, I was arrogant enough to think Western philosophy is rubbish.”

Eaton’s disillusionment was salvaged when he came across The Primordial Ocean by Professor Perry which convinced him if one were to understand symbolism, it would become apparent there was a common root of belief uniting cultures and traditions across the globe. This drew him into Christian mysticism which did not satiate his intellectual curiosities, so he progressed to Hindu Vedanta and Buddhism. He is, he says, “a universalist, although in a very special sense. One must have one religion and follow that. But, the comparison has been that your religion is the sun and the others are the stars. But to other people a star is a sun and they are all paths to God.”

So how does a young man with such a ravenous appetite for spiritual attainment incorporate his rather austere beliefs with his own existence? An indication is the story of how TS Eliot came to publish The Richest Vein, which Eaton describes as, “a book of spiritual inquiry, reflective of my thinking and my reading at the time. I was at a party and I went over and spoke to a girl who was standing alone, and she asked me what I do. I was an unemployed actor at the time, I did not want to say, so I told her I wrote and to my amazement she became very serious and asked what I was writing. She said she worked in Mr Eliot’s office and if I sent her my essays and if she liked them, she would show them to him.” When summoned to see Eliot, Eaton was so overwhelmed he, “could remember nothing about it afterwards except Eliot’s very long legs sticking out from underneath his desk!”

So is there a tension between the views he propogated and his lifestyle? “I remember a letter from a man who had read The Richest Vein and he wrote, “I’ve been trying to picture you, I think I can see you with flowing white hair and flowing white beard sitting on a mountain top in the Himalayas, meditating”! I was a very frivolous young man, as frivolous as can be. A Catholic priest came to Jamaica and on the plane had been reading The Richest Vein. He turned up at a party I was at. I was a little drunk, a girl sitting on my knee, and he stood there and looked down at me and said ‘you could not have written that book.’”

For Eaton, this was, “a very significant remark because I’ve never understood how the sort of person I was, could have written the sort of book I had written. But since then, this is a subject that has fascinated me all my life. This contradiction in human nature,” stresses Eaton, “is extraordinary, and almost inexplicable.”

Eaton married young, but the union was short lived and broke down soon before he left England for Jamaica, “because she was an actress and the theatre is not in general a sphere in which marriages last and partly because I had never wanted to get married. Catherine, my first wife, suggested it, saying it would be worth it even if it only lasted for a year or two.” We laugh at the incredulity of the scenario, but Eaton assures me that was the case, “because in those days if you wanted to be with somebody you’d have to go to a hotel and sign in as Mr & Mrs Smith and all the rest of it. I thought that’s wonderful, we could be husband and wife, and later I can go off on my adventures. It shows how immature I was, particularly because Catherine’s grandfather had been a bishop and we were married in a very fashionable church by a bishop. My mother’s only remark afterwards was, ‘What a farce!’”

We pause for a cup of tea and I meander from the living room to the hall as Eaton cajoles Shunan, his West Highland terrier, out of her hiding place underneath the majestic study table. I imagine many profound works travelled from Eaton’s thoughts and slipped onto paper at this very desk, to form the books we now read. The hallway is dominated by a large picture of Eaton as a young man, painted by his late second wife Corah who died of cancer nine years ago. I am astonished that I did not notice the portrait when I first entered, such is the grandeur with which the handsome young man greets any visitor.

In 1950, the domestic fragmentation of his first marriage inspired Eaton with a desire to escape London to which he had returned after a brief spell in Jamaica. Despite having no previous experience he was given a job lecturing in English at Cairo University as he was told, “It would do them good to speak to an Englishman”. Eaton was at this time, “in a very emotional state,” over Flo, a lady he had fallen in love with in Jamaica, and would compel his pupils with his emotional rendering of poetry. “While reading English love poetry, tears would run down my cheeks and one of my students said, ‘we love you sir, we thought all Englishman were cold hearted.’”

Eaton reflects upon his all-consuming love for Flo. “People say one should remember God, always, but you think how can you, you’re busy doing this or that. But for ten months I woke up thinking of this girl, I thought of her right through the day, I went to sleep thinking of her, and if you can think of another person all the time, you can certainly think of God all the time and still get on with living a normal life.”

While in Cairo, Eaton had become interested in the Sufi aspect of Islam and was reading widely on the subject. His journey towards embracing Islam is a composite tale of intent, witnessed in part by Dr Martin Lings, his colleague at the time. Soon after taking the shahadah, the declaration of faith, Eaton left for Jamaica. However, things did not work out with Flo and for some years Eaton called himself a Muslim, prayed occasionally, but it was not until years later, while he was working as a diplomat in India that his faith returned. He looks back on the years in Jamaica as “lost, wasted years. But on the other hand I am to some degree a fatalist and I feel I had to go through that.”

At the end of 1954, Eaton came back to England but found he missed Jamaica terribly. It was not long before he was re-introduced to an old acquaintance, a Jamaican artist, Corah Hamilton, who was living in London and they married soon after. The couple had three children and were married for 29 years until Corah’s death. “She remained Christian and I respected that.” And have his children accepted Islam? “They respect my beliefs. So far, I don’t think there’s any evidence they will come to Islam, except in the case of my younger daughter who is interested. I sometimes wonder if my own death may not provoke them into turning to that way.”

I ask Eaton about his view of women in Islam. “Certainly nowadays, women are the backbone of Islam, if you can compare a woman to a backbone! They are the strength of Islam. They are on the whole better Muslims than the men and since they bring up the children that is of great importance.” He goes further, attacking the leadership problems plaguing the Muslim world, “I’m sure I can offend many people with a terrible generalisation, but, in comparison with the womenfolk, I find a lot of Muslim men are basically weak.”

This is an interesting comment, in light of pervasive stereotypes that exist of submissive Muslim women. Eaton recounts the story of two English friends who having converted to Islam spoke of expecting to marry a nice little obedient Muslim lady, but after marrying, were found to be absolutely under their wife’s thumb.

Eaton’s first marriage may have been short-lived, but his devotion to his second wife Corah, is unquestionable. He is full of praise for her, “one remarkable thing was how successful Corah was, being the only black diplomatic wife. At functions her joke used to be, ‘as usual I’m the only black spot!’” Eaton proudly shows me a photograph of Corah with three prime ministers, two on one side and Harold Macmillan on the other, holding her arm and gazing at her admiringly while she smiles confidently into the camera. “When one very senior official came from London to visit us, we gave a party for him and Corah was as usual very charming. Afterward as he was being driven to the airport, he said ‘I’m happy to tell you your wife is a representational wife. I’m sorry to say your assistant’s wife is not!’ Representational meaning fit to represent Britain.”

While speaking at a conference in February, Eaton was outspoken in his views about immigration, declaring Britain must be cautious at large influxes of refugees, echoing sentiments favoured by David Blunkett. I ask Eaton his opinions on this subject and he begins by providing me with an anecdote. “When the first Immigration Bill came out in 1962, I was director of the UK Information Services at the colonial office. A cabinet minister came out to Jamaica and said, ‘You can say this very carefully to the [ Jamaican] Chief Minister, this Act to control immigration is not really directed at Jamaicans, they are after all of British culture, it is these hoards in the subcontinent we’re afraid of.’”

Eaton’s own view is that “it is time for the Muslims in Britain to settle down, to find their own way, to form a real community and to discover a specifically British way of living Islam.” But isn’t that exactly what we are doing? “The constant arrival of uneducated, non English-speaking immigrants from the sub-continent is disturbing to that, makes it more difficult.” Eaton is adamant, “This is no curry-island.”

I point out that the younger generation is defining its own British Islam, and wonder whether Eaton feels they are taking the right path. “Those I meet and talk to, yes. I’m told there is considerable wastage, young Muslims leaving Islam. But there’s always the very real possibility they will come back later in life when they begin to find their roots, and find the need for religion.”

I ask Eaton what Muslims can do, in the current political climate, to dispel any fear or attempts to demonise Islam. “The most important thing is to set an attractive example. Conversions to Islam in Malaysia, South India and elsewhere, came about because Muslims traders were such good men that people were drawn to belong. And now, as then, this is the most important thing because people judge, quite unfairly, by the few examples that they meet with.”

Eaton has a word of warning for the future. “It is essential to be realistic. Many Muslims nowadays, particularly the young Islamists are so totally unrealistic, it leads to disaster. If there’s a rock in your way and you refuse to recognise it, you’ll stub your toe.” And he is no less foreboding about civilisation as we know it, “I find it difficult to believe that this culture can go on as it is, all that much longer. It seems to me part of a familiar pattern of breakdown of civilisations and one sign of this is the speed by which events are occurring. The general speeding up of life. The biggest changes of the past 500 years have taken place certainly in my father’s lifetime, or even mine. That’s a very short period historically, so where we are going I do not know.”

words: Samia Rahman

image: Maeve Tomlinson

Bookmark this |

|

Add to DIGG |

|

Add to del.icio.us |

|

Stumble this |

|

Share on Facebook |

|

Share this |

|

Send to a Friend |

|

Link to this |

|

Printer Friendly |

|

Print in plain text |

|

Comments

0 Comments