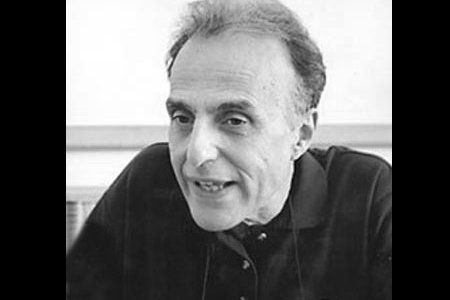

Table Talk with John Esposito

Issue 2 Nov / Dec 2003

John Esposito sees himself as a civilisational bridge builder. He has for the last 35 years been a student, researcher, and now professor of Islamic studies. He talks to Dilwar Hussain about his deep-seated affinity with the world’s most talked about religion.

Esposito was inspired by his PhD supervisor Ismail Faruqi, who he describes as, “somebody who moved from being a Palestinian nationalist for whom Islam was important, to becoming an Islamic intellectual scholar and activist within which he placed his Arab and Palestinian identity. He was like an intellectual father to me.”

A prolific writer having written and edited 30 books, Esposito has a passion for his work, “I set priorities, goals and deadlines and meet them, come hell or high water. This sn’t just my profession. I believe in what I do and the importance of it and I have a commitment towards it. I work very long days and tend to have a high level of energy which I channel into my work.” His schedule is gruelling, “When I wrote Islamic Threat I had even more pressures than now. I would wake up at 4.45am, fit in a six to eight mile run and then write from around 6.30am until about 7pm. I’ve always been someone who works six or seven days in the week and puts in very long hours.”

It has been ten years since Esposito became Director of the Centre for Muslim-Christian Understanding at Georgetown University. “I really enjoy the opportunity to make a difference. I do believe something now, which I didn’t when I was younger, that there’s a long range impact if you write certain kinds of pieces, and do that strategically. For example, if you write books on relevant topics that are accessible, published and kept alive over the years, your ideas and your writing can be part of the education of a whole generation, and so that’s what gives the ultimate satisfaction.”

Esposito started to write one of his most famous books, the Islamic Threat: Myth or Reality, during the first Gulf War. “My wife and I were watching coverage of the Gulf War and the more we watched the more we felt that this was falling into the pattern of presenting the war as a global Islamic threat. I sensed, from the collapse of Communism, a tendency to think in terms of a ‘clash of civilisations’. I wrote the book to basically state, and it’s amazing how many people read my book and didn’t get it, that Islam is not a threat, but some Muslims are. I said that there are extremist groups who are a threat, to their own societies primarily and their own people, but they are also a threat to the West. I also wanted to say that not only is Islam not a threat but the majority of Islamic Movements that participate within the system are not a threat. Of course I think these concerns have become prominent again in light of what’s happening today.”

The question now is whether there are more grounds to believe there will be a clash of civilisations? Esposito is equivocal, “I think there’s a danger of provoking one, in the sense that I think the rhetoric of Osama Bin Laden certainly declares that there is a clash. On the other hand, while the American and British administration have tried to distinguish between Islam and terrorists, there are certainly many in the West, particularly if you read the writings of people like Daniel Pipes, Steve Emerson , Martin Kramer, Bernard Lewis, Judith Miller, and Charles Krauthammer who like playing up the global Muslim ‘threat’.”

So, is the polarisation increasing? Esposito feels the so-called ‘war on terror’ needs to look at the global picture. “In addition to the military and economic aspects, it needs to be fought politically, with what some call political diplomacy. And part of political diplomacy is re-examining foreign policy. The Iraq war and post-war reconstruction are a critical challenge to the credibility of America and Britain in the Middle East and the broader Muslim world. Many Muslims have characterised the war on global terrorism as a neo-colonial attempt to redraw the map of the Muslim world. The reconstruction of Iraq, the emergence of an Iraqi-led process of self-determination and democratisation will determine whether the war in Iraq comes to be seen as a war of occupation or liberation. Equally important will be the failure thus far of the Road Map in the Palestine-Israel conflict as well as the next stage in the American-led war against global terrorism. Among the critical questions are: will it be focused, more clearly defined, multilateral rather than unilateral, enjoying broad-based Arab and Muslim support?”

Esposito has a deep and unique appreciation for Islam. “There is a level of faith and certitude among Muslims that even at the toughest of times is a remarkable gift. As a non-Muslim, this can arouse intrigue. There is much that is attractive and engaging at the intellectual, aesthetic and religious level. And one can engage with this without having to convert to it. If I’m brutally honest, some people can be very defensive, insecure, and suspicious and that’s regrettable. A colleague and I joke that it is like walking into a minefield, not knowing who you will upset! That’s still there.’”

Muslims, according to Esposito, “must remember who one is and what Islam once was, without denying the bad times – but to have the sense of pride, confidence and security that enables one to move on.” He believes Muslims in the UK have their own specific set of problems and need to find a sense of pluralism they can apply within and outside the community; otherwise the community will divide itself over important issues. “It’s all about empowerment. I get e-mails from young Muslims across the world asking advice on what they should study, and what is needed. I often say, ‘just remember that you are part of a community that needs to be empowered and being empowered means that people can play very diverse roles’. Not everybody needs to work for an Islamic organisation full time but they can be involved in a variety of professions (government, law, the media, business) where their presence and voice makes a difference and I think that’s the real key.”

Professor John L. Esposito is Professor of Religion & International Affairs, and Professor of Islamic Studies and Founding Director of the Centre for Muslim-Christian Understanding at Georgetown University. He is Editor-in- Chief of The Oxford Encyclopaedia of the Modern Islamic World and The Oxford History of Islam. His most recent books include Unholy War: Terror in the Name of Islam, What Everyone Needs to Know About Islam, and The Oxford Dictionary of Islam.

Remembering Edward Said

A seminal voice for the Occident, Edward Said who died on September 25 2003, challenged Orientalist pre-conceptions held by the West and, according to Dr Bobby Sayyid, gave rise to the birth of post-colonial studies as we know it.

Edward Said was probably one of the most influential intellectuals of recent times coming out of the Islamicate world. His background was Palestinian, Christian, Francophone and well-to-do. His work, however, transcended his upbringing. Instead of being another apologist for imperialism, another ‘self-hating colonial subject’, Said criticised the relationship between western knowledge and western power. He demonstrated that what western culture saw in the rest of the world was a reflection of its own fantasies and anxieties. In his masterpiece, Orientalism, Said argued that western knowledge was implicated in western imperialism not simply through the biographical details of spies and colonial functionaries who took up chairs in universities teaching anthropology and area studies, but at a concep

conceptual level, where western knowledge legitimates western power. We can see this in Iraq, where fantasies of weapons of mass destruction and a grateful Iraqi people were used to justify the occupation of the country. Said articulated what many people in the Islamicate world felt but found it difficult to give expression to.

Not only will Edward Said be remembered for unsettling the cosy and frankly racist assumptions by which west produced knowledge about the rest, but also for his unrelenting courage. He advocated Palestinian rights in one of the most anti-Palestinian countries in the world. He was accused by Zionists of being a terrorist (but then who is not nowadays, it is hard to be independent minded without being labelled a terrorist). His sterling service to the cause of Palestinian nationalism was rewarded by Yasser Arafat having his books banned from the West Bank and Gaza, as it became clear that Said was highly critical of the so-called Oslo Peace process. His criticism of the Western intellectual enterprise made him unpopular with the old (and young) fogeys who rarely hesitated to condemn him even though they showed little sign of understanding his arguments.

Even though Edward Said never really understood or cared for the global awakening of Islam, many Muslims will mourn the death of an ally, a champion and an inspirational writer.

Dr Bobby Sayyid, University of Leeds.

“We cannot resist American imperialism through rage and hate. We can do little without taking a few steps towards putting our own house in order.”

It’s that time of the year when we Muslims pay extra attention to spiritual matters and devote much more time to prayer and reading the Qur’an. But contemplation during Ramadan need not be focused only on spiritual concerns. It is also the time to think of others, less fortunate, than ourselves; and a time for introspection and self-criticism. So when you open your fast in relative comfort, think of our long suffering brothers and sisters in Iraq. Most of them will spend Ramadan without basic amenities such as electricity and water and in a total state of insecurity. From the perspective of the people of Iraq, one form of home grown oppression has been replaced by another – the new global tyranny of the United States.

Iraq provides us with an excellent example of the current state of Muslim plight. Internally, the Muslim world seems to be imploding with obscurantism and strife, rage and violence, and impotence and hopelessness. Externally, we are under severe pressure from an arrogant hyperpower hell-bent on pursuing its own selfish interests and rendering everything in its self-image.

Under Saddam Hussein, Iraq became an utterly indefensible entity - unspeakably brutal, totally divorced from global realities, a personal fiefdom of a clan and a barbaric family, and isolated even from the rest of the unsavoury Arab world. Of course, colonialism and western power politics played an important role in creating this vicious state. But we can’t lay all the blame on others and history. Saddam Hussain was, and remains, a product of our own culture. While much more brutal, he is not that much different from all the other despots in the Arab world.

We need to ask why Muslim societies are so prone to despotism and dictatorships, still so deeply anchored in feudalism and tribalism. Are we getting the leaders we deserve? Why is routine torture so prevalent in Muslim countries? Why are basic human rights, including the rights of women, so starkly missing from Islamic societies? What role have we played and are playing in our own destruction?

These are uncomfortable questions. We do everything to try and avoid them. As I know from my own experience, we would much rather wallow in nostalgia, recount the glories of our ‘Golden Age’, and insist on how Islam provides an answer to everything, than take an objective and critical look at our own shortcomings. But unless we deal with these questions honestly, with an open mind, we can do nothing about the other side of the equation: the new aggressive brand of American imperialism.

It is important to appreciate how significantly the character of the US has transformed under the Bush administration.

The rejection of the Kyoto Protocol, the Anti-Ballistic Missile treaty, the Comprehensive (Nuclear) Test Ban treaty, and the opposition to the creation of the International Criminal Court as well as the STAR wars initiative, which puts nuclear weapons into space, provide a good indication of this. But the real direction of American foreign policy was made clear even before Bush came to power in the famous Neo-Conservative Manifesto, The Project for a New American Century. Written by some of the same people who are now in power – including Vice-President Dick Cheney and Secretary of State Donald Rumsfeld – it is, not to put too fine a point on it, a rationally thought out plan for world domination.

Against this background, it becomes quite irrelevant whether Iraq did or did not have weapons of mass destruction. The decision to invade Iraq had been made a long time ago, September 11 not withstanding. The US already had a very clear view of how the world had to change to protect and promote America’s interest, and Iraq was the first critical step. The war on Iraq, no matter what Tony Blair may claim, had entirely selfish reasons: oil and the extension of America’s military outreach. The fact that Iraq was judged to be in possession of significant stocks of chemical and biological weapons which might find their way in to the hands of al Qaeda and other nefarious groups was only a minor item on the agenda.

The question we need to address regarding our own Prime Minister is not whether he did or did not embellish the infamous weapons of mass destruction dossier, although even on this issue the Hutton Inquiry, in the best traditions of British Parliamentary inquiries, will not provide us with any clear answers. The question we need to ask is this: why does Blair so passionately think that promoting American political hegemony and economic and cultural interests around the globe are beneficial for Britain?

But Blair is only a minor figure in all this. America would have invaded Iraq even without Britain. Resisting this kind of determination is not going to be easy for Muslims. Certainly, we cannot resist American imperialism through rage and hate and empty slogans about Islam’s inherent superiority. Equally, we can do little without taking at least a few steps towards putting our own house in order.

Ramadan, above everything else, is about hope. Hope in the Mercy and the Grace of God. Once, Baghdad was the centre of Islamic culture, of science and philosophy, art and literature, a beacon of human progress. Let us hope and pray during this blessed month of Ramadan that one day soon Baghdad plays that role again. But let us also work out a sane strategy – indeed a ‘Project’ – to take us from here to there. As the beloved Prophet said, trust in God and at the same time tie your camel!

Bookmark this |

|

Add to DIGG |

|

Add to del.icio.us |

|

Stumble this |

|

Share on Facebook |

|

Share this |

|

Send to a Friend |

|

Link to this |

|

Printer Friendly |

|

Print in plain text |

|

Comments

0 Comments