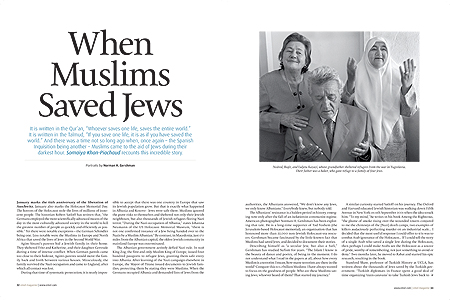

When Muslims Saved Jews

Issue 64 January 2010

It is written in the Qur’an, “Whoever saves one life, saves the entire world.” It is written in the Talmud, “If you save one life, it is as if you have saved the world.” And there was a time not so long ago when, once again – the Spanish Inquisition being another – Muslims came to the aid of Jews during their darkest hour. Somaiya Khan-Piachaud recounts this incredible story.

(This feature was first published in emel for issue 64 - January 2010)

January marks the 65th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. January also marks the Holocaust Memorial Day. The horrors of the Holocaust stole the lives of millions of innocent people. The historian Robert Satloff has written that, “the Germans employed the most scientifically advanced means of the day in the most culturally advanced society in the world to kill the greatest number of people as quickly and efficiently as possible.” Yet there were notable exceptions – the German Schindler being one. Less notable were the Muslims in Europe and North Africa that saved the lives of Jews in the Second World War.

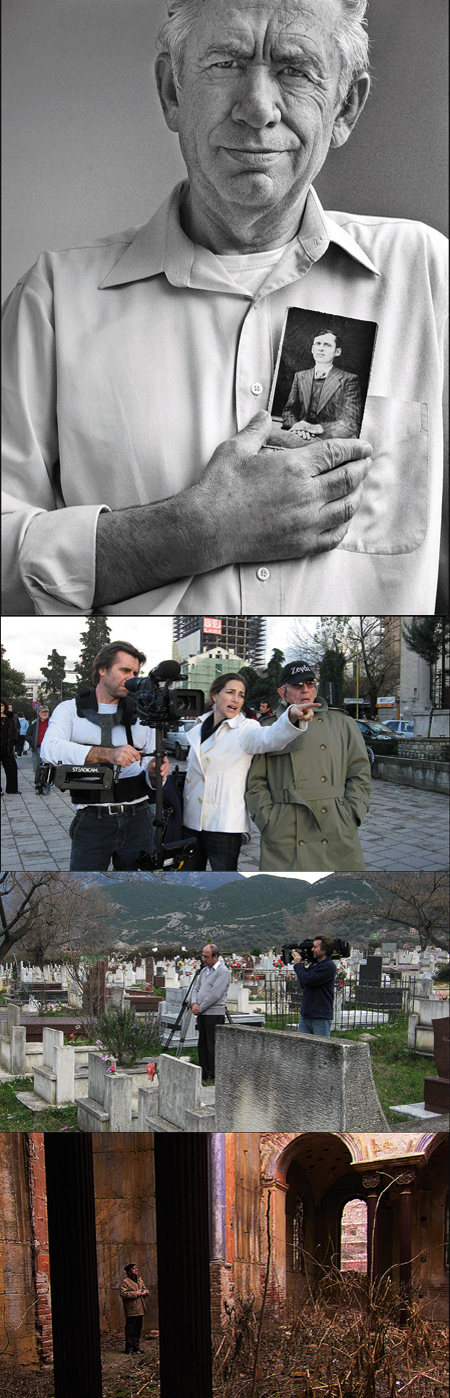

Agim Sinani’s parents hid a Jewish family in their home. They sheltered Fritz and Katherine, and their daughter Gertrude during a time of intense conflict. When German patrols came too close to their hideout, Agim’s parents would move the family back and forth between various houses. Miraculously, the family survived the Nazi occupation and came to England, after which all contact was lost.

During that time of systematic persecution, it is nearly impossible to accept that there was one country in Europe that saw its Jewish population grow. But that is exactly what happened in Albania and Kosovo - Jews were safe there. Muslims ignored the grave risks to themselves and sheltered not only their Jewish neighbours, but also thousands of Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi terror. “During the Nazi occupation of Albania,” states Johanna Neumann of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, “there is not one confirmed instance of a Jew being handed over to the Nazis by a Muslim Albanian.” By contrast, in Macedonia, just 170 miles from the Albanian capital, the oldest Jewish community in mainland Europe was exterminated.

The Albanian government actively defied Nazi rule. In 1938 King Zog, the first and only Muslim King of Europe, issued four hundred passports to refugee Jews, granting them safe entry into Albania. After learning of the Nazi campaign elsewhere in Europe, the Mayor of Tirane issued documents to Jewish families, protecting them by stating they were Muslims. When the Germans occupied Albania and demanded lists of Jews from the authorities, the Albanians answered, “We don’t know any Jews, we only know Albanians.” Everybody knew, but nobody told.

The Albanians’ resistance is a hidden period in history, emerging now only after the fall of an isolationist communist regime. American photographer Norman H. Gershman has been exploring that tale. He is a long-time supporter of Yad Vashem (the Jerusalem-based Holocaust memorial), an organisation that has honoured more than 22,000 non-Jewish Holocaust-era rescuers. Gershman became fascinated by the little-known fact that Muslims had saved Jews, and decided to document their stories.

Describing himself as “a secular Jew, but also a Sufi,” Gershman has studied Sufism for years. “The Islam I know is the beauty of dance and poetry, of being in the moment. I do not understand what I read in the papers at all, about how every Muslim is a terrorist. I mean, how many terrorists are there in the world? Compare this to 1.2 billion Muslims. I have always wanted to focus on the goodness of people. Who are these Muslims saving Jews; whoever heard of them? That started my journey.”

A similar curiosity started Satloff on his journey. The Oxford and Harvard educated Jewish historian was walking down Fifth Avenue in New York on 11th September 2001 when the idea struck him. “To my mind,” he writes in his book Among the Righteous, “the plume of smoke rising over the wounded towers conjured to me the chimneys of the [Nazi] death camps, two examples of killers audaciously perfecting murder on an industrial scale... I decided that the most useful response I could offer to 9/11 was to combat Arab ignorance of the Holocaust... If I could tell the story of a single Arab who saved a single Jew during the Holocaust, then perhaps I could make Arabs see the Holocaust as a source of pride, worthy of remembering, not just something to avoid or deny.” Two months later, he moved to Rabat and started his epic research, resulting in the book.

Stanford Shaw, professor of Turkish History at UCLA, has written about the thousands of Jews saved by the Turkish government. “Turkish diplomats in France spent a good deal of time organizing ‘train caravans’ to take Turkish Jews back to Turkey... In addition to providing material assistance to Turkish Jews persecuted in France and other countries occupied by the Nazis in Western Europe, Turkey also helped East European Jews persecuted in countries such as Greece, Lithuania, Romania, Hungary, Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. Right from the start of the war, the Turkish government permitted the Jewish Agency to maintain rescue offices at hotels in Istanbul.”

Gershman’s project began as an individual quest. He first travelled to Albania in 2002 to photograph and document the stories of those who were ‘righteous’ in the face of despotism. Over a five-year period he sought out, photographed, and collected individual stories, which he then published in a photo book titled ‘Besa: Muslims Who Saved Jews in World War II’.

“These were simple people, who never thought of themselves as being heroes. They risked everything,” Gershman says. “It’s a wonderful story. I am delighted to be able to bring light on the deeds they did. Whenever possible I have sought out the people who sheltered the Jews. Many have since died, and in those cases I have photographed their spouses or their children. My portraits reflect their religious and moral convictions, and their courage.”

Upon his return from Albania, Gershman contacted producer Jason Williams. The two worked together 25 years ago and have a shared history - Jason was married to Norman’s daughter, and although the marriage did not last the two men remained close. They set about creating a documentary entitled God’s House – a behind-the-scenes look at Gershman’s painstaking search for Albanians who rescued Jews. Like the filmmaker himself, the entire film serves as a poignant emblem of the intersections of the Abrahamic faiths: at one point Gershman, a Jew in search of Muslims, prays in Arabic in a Christian Church in Tehran.

Apart from exploring the individual acts of courage, the film documents and defines Besa (meaning obligation), an ancient tradition specific to Albania. The documentary is full of stories of fathers and sons, of the duties and obligations passed from one generation to the next. “One of the main strands of the film,” Williams explains, “focuses on a Muslim son, Rexhep Hoxha, who is determined to fulfil the Besa agreed to by his father;

he is equally determined not to hand on that obligation to his own son.” The film also tells the story of a Jewish son who was brought to Albania and “saved by this surrogate Muslim father…These stories of fathers and sons are very tightly interwoven,” Williams adds.

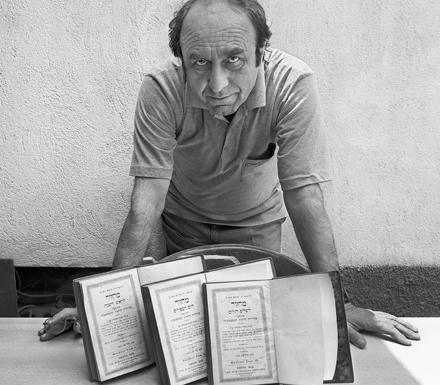

The tradition of Besa still compels modern-day Albanians to fulfil past promises. God’s House follows Rexhep Hoxha, an Albanian toyshop owner who has an interesting family heirloom - a set of beautifully bound books written in Hebrew, entrusted to his father by a Jewish family headed by Nissim Aladjem. Nissim had promised to return for these treasured possessions, but for 66 years the Hoxha family waited hoping that one day the Aladjems would reclaim it. With no sign of the Aladjems, Rexhep promised his father that he would return the books. A generation after the Hoxhas sheltered Nissim, Sara and their 10-year-old son Aron, Rexhep journeys to Jerusalem in search of Aron.

Although the film uncovers the past, one cannot help but feel that it may have important present-day consequences as well. Williams is hopeful the film, which will premier this year, will provide a basis for dialogue, “Here is an instance where we have fully documented a Muslim community which recognised the coming of the Holocaust, responded to the Holocaust, and worked to give refuge to Jews. That message does not exist anywhere else. So I think it has this very profound ability to perform a useful and very positive basis for dialogue.”

Rexhep Rifat Hoxha, with Hebrew books left behind by a Jewish family his father sheltered. The documentary God’s House explores his determination to fulfil the Besa (obligation) agreed to by his father in returning the books to their rightful owner.

Even at the age of 77, Gershman says that his work documenting those who helped save Jewish lives is not complete. “How are we ever going to find these people decades down the line? Contact has been lost between rescuers and refugees. There is so much sadness. Many Jews do not want to remember. If I find, or someone tells me, about a family who saved a Jew, I will seek them out and take their portrait. This is my mitzvah (human kindness).”

For his book Satloff spoke to Jews who had escaped persecution. He recounts the story of Yehuda Chachmon, a Libyan Jew interned in an Italian camp in Giado. “The Arab camp guards opted out of the sadistic torture inflicted on Jews and other prisoners by the Italians. Of the 2,600 Jews in the Giado camp 562 died in less than a year. The Italian guards treated the Jews with brutality; the attitude of the Arab guards under the Italians was excellent. They even found secret ways to ease our discomfort.”

In Algeria, pro-Jewish sympathy was led by religious scholars like Abdel Hamid Ben Badis, founder of the Algerian League of Muslims and Jews who was an “intensely devout man with a modern, open and tolerant view of the world.” Shaykh Taieb el Okbi was another leader who had close ties to the Jews. When French pro-fascist groups were urging Algerian Muslims to persecute the Jews, Shaykh Taieb issued a fatwa prohibiting that. And from pulpits of Algerian mosques imams issued instructions to their followers to defy the fascists and behave honourably towards the Jews.

The Jewish resistance leader in Algiers, Jose Aboulker, testified how when “Jewish goods were put up for public auction, an instruction went round the mosques, ‘Our brothers are suffering misfortune. Do not take their goods.’ Do you know other examples of such an admirable, collective dignity?”

In Morocco, Satloff identifies Sultan Muhammad V as a saviour of the Jews. Though he had little independence from the French, in his view the Vichy anti-Jewish laws breached a fundamental tenet of Islam. “Muhammad V offered vital moral support to the Jews of Morocco. When the French authorities ordered a census of all Jewish-owned property, the sultan arranged a group of prominent Jews to sneak into the palace, hidden in a covered wagon so he could meet them away from the prying eyes of the French. He promised the Jews he would protect them.” Once in a public gathering the sultan declared, “I must inform you that, just as in the past, the Israelites will remain under my protection. I refuse to make any distinction between my subjects.”

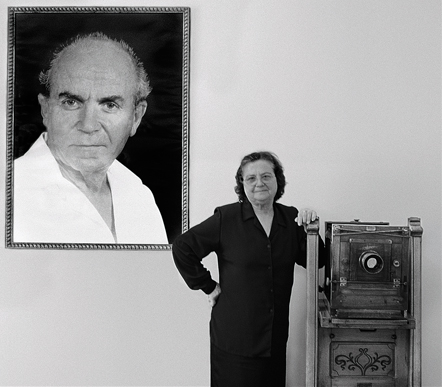

Drita Veseli, in front of a photographic portrait of her late husband, Refik. The family of Vesel and Fatime Veseli were amongst the first Albanians to be recognised by Yad Vashem for saving the lives of Jews during the Second World War.

Satloff tells a similar story in Tunisia. There, the wartime rulers Ahmed Pasha Bey and his cousin Moncef Bey offered vital public support for Jews facing Vichy persecution. “They regularly warned Jewish leaders of German plans, helped Jews avoid arrest orders, intervened to prevent deportations, and even hid Jews so they could evade the Germans. Moncef Bey is remembered fondly by Tunisian Jews. “He gave the Jews equal treatment,” declared Shlomo Barad. “He did not allow them to be discriminated.”

Satloff recognises that a great many North Africans were complicit in the Nazi and Vichy persecution, but he had set out to uncover those brave people who stood by their Islamic principles despite personal danger. Men like Ali Sakkat, who opened his farm to sixty Jewish escapees from a labour camp and hid them until liberation by the Allies; Khaled Abdelwahhab who scooped up several families in the middle of the night and took them to his countryside estate to protect them. In this day, when relations between Jews and Muslims are fraught and tense, the distinctive works of Gershman, Satloff and others may bring healing and enable a rapprochement. As Satloff writes in his book, “this is the most hopeful story I have ever told. Recapturing these lost stories from the Holocaust’s long reach into Arab lands offers people of good will among each community — Arab and Jewish — a way to look through the lens of one of the most powerful narratives in history and see each other differently. It is the most positive response I could offer to the events of that Tuesday morning in September.”

(From top to bottom) Agim Sinani, holding a photograph of his father. His family sheltered a Jewish family of three during the war. Above right, scenes from the documentary God’s House following the photographer’s journey.

______

For more information:

Among the Righteous: Lost Stories from the Holocaust’s Long

Reach into Arab Lands, by Robert Satloff

Photo book: www.eyecontactfoundation.org/BESA

Documentary: www.godshousefilm.com

Missing Pages

by the Exploring Islam Foundation

Muslims voice their solidarity with Jews by today (Monday 24 January) launching “Missing Pages,” a campaign highlighting forgotten stories from the Holocaust. The Exploring Islam Foundation campaign challenges misconceptions about the relationship between Jews and Muslims and is supported by Chief Rabbi Lord Sacks.

This feature was first published in emel for issue 64 on January 2010>

Bookmark this |

|

Add to DIGG |

|

Add to del.icio.us |

|

Stumble this |

|

Share on Facebook |

|

Share this |

|

Send to a Friend |

|

Link to this |

|

Printer Friendly |

|

Print in plain text |

|

Comments

2 Comments

1

Ifti

26 Oct 14, 07:11

Israelis do not remember that in the year of the expulsion, 1492, the country that opened its gates to the exiles from Spain – without constructing prison facilities for them – was Ottoman Turkey. “The only oasis of the tribe, for which all other countries are hell as far as it is concerned,” was the way Ze’ev Jabotinsky described what Ottoman Turkey was to its Jewish subjects for centuries (from “Jews in Turkey,” Odessa News, February 14, 1909).

After the Turkish vessel Mavi Marmara sailed as part of the flotilla to Gaza, the level of Israeli hostility to Turkey was similar to the level of ignorance in everything having to do with the shared past of the Turks and the Jews. That is why these statements by Jabotinsky will probably cause a feeling somewhere between suspicion and amazement. After all, what do we know about the Turks and the Jews other than the fact that the Turks once ruled the Land of Israel and had the gall to refuse to hand it over to Herzl?

IA

London School of Isla

2

Umm Abdullah

23 Sep 12, 08:19

Wonderful story. Thanks for sharing it.