A Century of Service

Issue 76 January 2011

Very few Islamic institutions in the UK can commemorate a centenary. East London Mosque is one of them. It was founded on pluralistic ideals and had prominent non-Muslims amongst its founders. Jamil Hussein plots the history of the mosque and looks at whether it has lived up to its ideals.

Photography by Rehan Jamil

Panerai Luminor 1950 GMT 3 Days Replica

It is one of the biggest mosques in the UK and - despite being just an adhan away from London’s financial district - in one of the poorest parts of the country. But Whitechapel’s iconic mosque was actually conceived in a glitzier part of town: the Ritz Hotel in Mayfair to be exact. On 9th November 1910, Right Honourable Syed Ameer Ali, Aga Khan III and writer Sir Theodore Morrison met at the hotel to lay the foundations of what is now known as the East London Mosque (ELM). The meeting concluded with the participants creating a fund – The London Mosque Fund – to build a mosque in the capital. The founders hoped the mosque would create harmony between the faiths and be a symbolic gesture to Muslims in the Empire. Syed Ali was the main instigator. He was a keen supporter of the Empire and the first Muslim privy councillor in British history - the second being Sadiq Khan a century later in 2009. “The inspiration to build a mosque came from Syed Ali, who wanted to bring Muslims and non-Muslims together. But there was a collective vision amongst the founders, which included non-Muslims, to work together and build a mosque at the heart of the British Empire,” says Shaynul Islam, ELM’s assistant executive director.

Non-Muslims connected with the mosque have included Lord Rothschild, Lord Lamington, Lord Ampthill, Sir Frederick Sykes, Earl Winterton, Sir John Woodhead and Sir Ernest Hotson. Prominent Muslim figures Marmaduke Pickthall and Yusuf Ali – the two famous translators of the Qur’an – were also involved in the early stages. Initially, jumm’ah (Friday) prayers were held at hired halls around West London, catering for ambassadors and Muslim dignitaries in the area. But the demand for prayer facilities was more urgent in the East.

The influx of Muslim workers and merchants from London’s Docklands meant East London was a prime location for a mosque. Again, halls were hired, including Kings Hall on Commercial Road - a Yiddish Theatre that had once seen Vladimir Lenin give a talk. The switch to the other side of London attracted local volunteers to the mosque. They helped in the day-to-day operations and later organised into a group called Jamait-ul-Muslimin.

Mohammed Toboris Ali has been a volunteer since 1977. He organises volunteer stewards for Friday prayers when around 5,000 worshippers turn out. When the 69-year-old first started volunteering, he used to drive local children to the mosque every weekday evening to their Arabic classes. “I get 30-year-olds stopping me in the street now. They hug me and say ‘Don’t you remember me? You used to take me to the mosque.” Ali said those moments make him realise the benefit volunteers have on the community. “I hope we can set an example to others, especially the youth, of how you can help in the community. And also, hopefully, get our good deeds rewarded by Allah.”

In 1940, three renovated houses on Commercial Road were bought, and a year later East London Mosque opened. It became a magnet for new migrant workers coming to London to rebuild the city after the war. Even the mosque was damaged during the Blitz and funds from the War Damage Commission were allocated for its repair. Bengali Muslims, working mainly in the garment and restaurant business, were the biggest post-war immigrants to the area. Today, although Bengalis are still the majority, sermons are given in several languages, reflecting the ethnic mix of the congregation.

The mosque suffered a setback when the Greater London Council made a Compulsory Purchase Order on the building to expand the A13 highway in 1975. In return, the mosque was given temporary facilities in its current location on Whitechapel Road, next to the Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue. It meant the local community had to start raising funds again. But it gave them the creative scope to build a purpose-built mosque complete with dome and minarets. That dream was finally realised in 1985. It was also the first mosque in the UK to project the adhan, which the local authority planners needed to be convinced about. “The management got the planners to come on a Sunday and at 12pm the bells from the local church started chiming. The trustees were trying to show that the call to prayer wasn’t much different,” says Islam. By the turn of the century, the Muslim population continued to grow, and so did the mosque. A new wing - the London Muslim Centre (LMC) - was completed in 2004. Prince Charles helped lay the foundation of the LMC and cited the history of the mosque and the “many non-Muslims amongst its ranks.”

Replica Watches Although non-Muslim involvement in the management has long ceased, work with people from other backgrounds is still very much on the agenda. The mosque has been involved in inter-faith programmes and local community projects. It works with the Council on various projects, assists on health and drugs issues with the Primary Care Trust, undertakes employment and training programmes and has a pro bono legal service for both Muslims and non-Muslims. “There’s no question it benefits the whole community. The mosque leads on promoting community cohesion,” says Neil Jameson, executive director of civil engagement group London Citizens. “It has been an outstanding active participant in the work we do.”

ELM was a founding member of London Citizens. It helps with the organisation’s campaigns, such as “Living Wage” – to get companies paying £2 more than the minimum wage - and “CitySafe,” which tackles street crime. The mosque also helped Citizen UK (the national incarnation of London Citizens) with an event that hosted the leaders of the three main political parties before the general election. Jameson said London Citizens relies on the mosque for many things and it has been important in making events and meetings successful. Ties with local non-Muslim organisations were fomented in the 70s when a young restaurant worker, Altab Ali, was killed in a racist attack just yards from the mosque. The local community, from all backgrounds, rallied together to oust the far right influence.

But in recent months, the noise of far right boots has resurfaced. The English Defence League (EDL) threatened to march to the mosque. But again, the community stood united and the march was cancelled. Islamophobia has risen in recent years because of 7/7 and other terrorist actions by extremists around the globe. But the mosque believes the rise in anti-Muslim rhetoric in certain sections of the media and the internet is spurring far right groups even further. “There is no doubt that anti-Muslim bigotry in the media is fuelling the likes of the EDL, who have cited the work of certain right-wing newspapers and commentators as a prime source for attacking the ELM,” says Dilowar Khan, the director of the mosque.

Upto 25,000 people a week come to the ELM and LMC, and many more attend the Eid prayers. Ramadan is a particularly busy time with lots of activities and a complete recitation of the Qur’an during tarawih.

Critics of the mosque say it has invited extremist speakers and question its close ties with a grassroots group called Islamic Forum Europe (IFE), which some accuse of being “fundamentalist,” and Jamaat e-Islami, an Islamic political party in Bangladesh. “Despite all the attempts to smear us, there has never been a single example of extremist talk from the mosque itself,” says Khan. “On rare occasions it may be that someone speaking at an event for which a room or hall has been hired says something we neither agree with nor approve of.” To stop this, the mosque now takes a more stringent approach to vetting speakers and materials when third parties use its facilities. On the IFE, Khan says the group provides voluntary help to the mosque and is a tenant, with many others, in the business wing of the LMC - the IFE itself denies the “fundamentalist” tag and points out its many partnerships with non-Muslim groups. “There is no organisational or structural link with the Jamaat-e-Islami,” adds Khan.

Neil Jameson from London Citizens says he has been working with the mosque for 15 years and accusations of it being “extreme” are “completely foreign” to him. “Absolutely, they are moderate. They are interested in community life and are very committed to it,” he says, adding that criticism of the mosque tends to come from outsiders.

The mosque hopes increased transparency will help dispel some of the negative views. Sermons are now available online and visitors are free to tour the mosque and talk about their concerns, even the media. “Fortunately, people who come into regular contact with us, who work with us, know what we are really like,” says Khan. “We want to make our community and society a better place by providing wider services and working with others. We are determined to do that.”

A thoughtful Dr Abdul Bari, the current Chairman, reflects on the history of the ELM.

The Mosque was opened on Friday 1st August 1941 and the prayer was led by Shaykh Hafiz Wahba, Ambassador of Saudi Arabia.

The services the mosque provides will increase this year when construction of the nine-story Maryam Centre is completed in the second half of 2011. Already the mosque has a designated nursery, secondary school, gym and funeral service but the new building will prioritise the needs of women - the first of its kind in the UK. It will add to its existing women’s advice centre with a women-only fitness gym, clinics, domestic violence support and counselling rooms. The mosque believes the expansion will make it the biggest in Europe in terms of congregation – something the original founders would have been proud of, says Khan. “It has definitely lived up to the ideals and expectations of its founders. The mosque was founded out of co-operation and mutual understanding between Muslims and non-Muslims,” he says. “The universal understanding we all hold as human beings is important. We have to work towards the common good, even if there are some conflicting views in society. As long as we can work together to make our society a better place, I think that is what matters the most.”

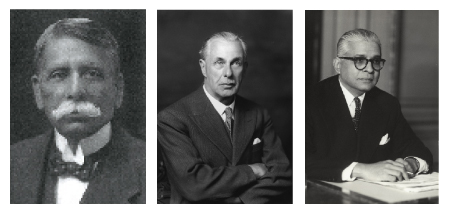

From left to right - The Right Honourable Sir Syed Ameer Ali arranged a meeting at the Ritz Hotel in November 1910 to establish a fund for the purpose of building a mosque and centre. Sir John Woodhead served on the East London Mosque Trust for almost 14 years. Muhammad Ikramulla, the Pakistan High Commissioner, was Chairman of the Mosque Fund from 1952.

The Development

The East London Mosque has gone from a rented hall, to a purchased house, to a purpose built mosque, to a major centre

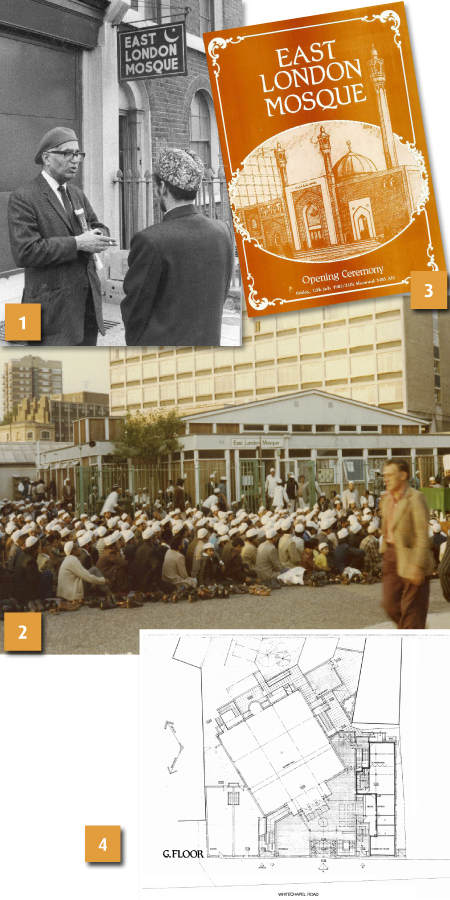

1) The original mosque and sailors’ hostel was based in a row of three houses at 444-448 Commercial Road.

2) In 1975 the mosque had to move to temporary buildings in Fieldgate Street until a permanent purpose built mosque could be constructed.

3) It took another ten years before the purpose built mosque in Whitechapel was officially opened.

4) The new mosque was designed by John Gill Associates and constructed by W.J.Mitchell & Sons.

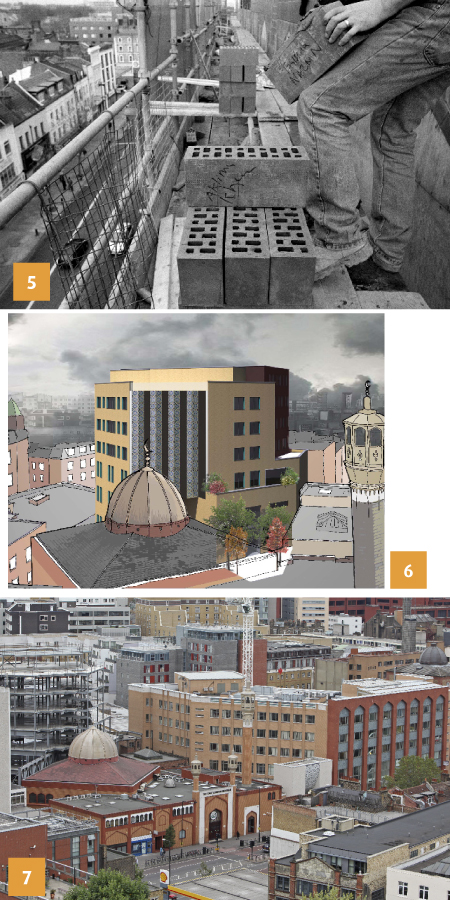

5) As the local community grew, the need for a larger mosque space and community centre became evident. The local community raised funds by literally purchasing bricks. The London Muslim Centre was opened in 2001.

6) The Maryam Centre will focus on women, offering extensive services and facilities.

7) The ELM (foreground), the LMC (right) and the Maryam Centre (under construction) are a now a local landmark.

Bookmark this |

|

Add to DIGG |

|

Add to del.icio.us |

|

Stumble this |

|

Share on Facebook |

|

Share this |

|

Send to a Friend |

|

Link to this |

|

Printer Friendly |

|

Print in plain text |

|

Comments

0 Comments